Volume 24 number 1 article 1311 pages 1-20

Received: Aug 13, 2025 Accepted: Dec 09, 2025 Available Online: Feb 16, 2026 Published: Mar 02, 2026

DOI: 10.5937/jaes0-60816

COMPREHENSIVE EVALUATION OF INDIAN STANDARD CODES AND CURING APPROACHES FOR GEOPOLYMER CONCRETE

Abstract

Geopolymer Concrete (GPC) is a sustainable alternative to Ordinary Portland Cement (OPC), reducing global CO₂ emissions by 8-10% using industrial by-products such as fly ash, slag, metakaolin and silica fume. This approach not only reduces landfill waste and environmental pollution but also aligns with global sustainability goals. Extensive research highlights the increased sustainability of GPC, which includes excellent resistance to chemical corrosion, fire and elevated temperatures, rapid strength development and long-term structural stability. This study undertakes a comprehensive review of the existing literature on GPC, with a special focus on the applicability of Indian Standard (IS) codes for mix design and optimization of curing methods. However, despite significant research progress, GPC remains excluded from building codes in many regions. Given the absence of a dedicated design code for GPC, the review evaluates standardized test protocols for fresh and hard properties tailored to India's climatic conditions. The data for this analysis were systematically extracted from the Scopus database and non-Scopus journals, providing a solid foundation for critical evaluation, presented in a consolidated way to give a clear and focused context. This study validates GPC as a sustainable alternative to conventional concrete in India. However, optimization of mix design parameters, curing methods and durability performance, along with standardized guidelines, is required for widespread adoption. These findings provide important insights for researchers and practitioners to develop environmentally friendly construction technologies.

Highlights

- The study summarizes state of the art research along with provisions of Indian standard codes for geopolymer concrete adoption.

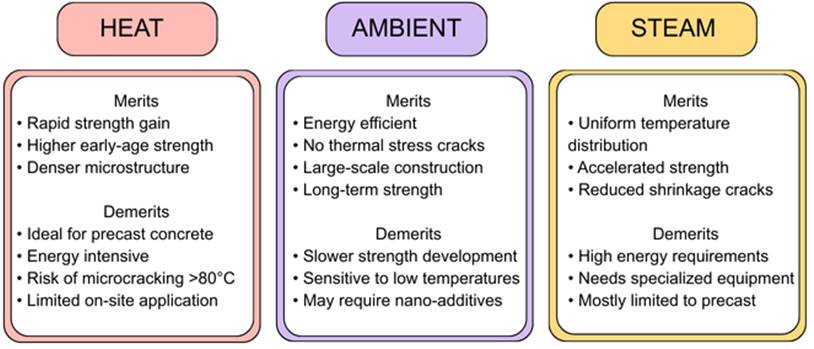

- Effective curing methods of geopolymer concrete for Indian weather conditions with their merits and demerits are discussed.

- The study extracts feature of curing approaches implemented by researchers through a systematic summary of binder materials’ influence on curing methods.

Keywords

Content

1 Introduction

Portland cement has been used in the construction sector as the major cement in concrete, but its carbon footprint and the environmental burden have triggered scientists to seek environmentally friendly alternatives. Geopolymer Concrete (GPC) has begun to get attention as an innovative material, which is manufactured using alkali activation of aluminosilicate materials like low-calcium fly ash and Ground Granulated Blast Furnace Slag (GGBS). Sodium or potassium-based alkali solution can be used to prepare GPC that provides sufficient strength to the mix (Rajamane et al., 2011; Provis et al., 2015). Using this, the binding system is obtained through a process termed geopolymerization that sets at room temperature and emits very low amounts of CO2 when compared to the traditional procedures of cement manufacturing (Davidovits, 1993). The output product has a high compressive strength and low drying shrinkage with an exceptional chemical attack resistance to sulfates and acids (Rangan, 2014), rendering it advantageous in adverse conditions of marine structures, wastewater plumbing systems and industrial structures (Davidovits, 1990). In addition to the reduced amount of waste, GPC is claimed to have less energy demands, less dependency on landfills, making a stronger case in sustainable development since it will reuse industrial by-products such as fly ash and slag in the mix (Rajamane et al., 2011) addressing United Nation’s (UN’s) Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) including Industry, innovation and infrastructure (SDG 9), Sustainable cities and communities (SDG 11), Responsible consumption and production (SDG 12), Climate action (SDG 13).

GPC has evolved as a more sustainable replacement of the conventional Portland cement concrete to reduce CO2 emissions and increase resource utilization (Anuradha et al., 2011; Lloyd and Rangan, 2010). The cement industry in India has gained immense growth with an output of more than 400 million tons in 2023, placing India as the second-best cement producer in the world after China. As a consequence, there is a nearly 4 times increase in CO2 emissions since 2000, up to 177 million Metric Tons (Mt) CO2 in 2023: this contributes to 6 percent of India's total fossil and industrial emissions and 11 percent of global cement emissions. Owing to the increasing demand for infrastructure, the emissions would increase even further (Ian Tiseo, 2025). To address the impact of a large level of cement production on an increase in greenhouse gas emissions, GPC is the right solution for attaining environmental and economic sustainability. In order to address the peculiarities of the chemical behavior and curing specifications of the GPC, a specific standard code should be developed to promote the usage of GPC. IS 10262:2019 is the Indian standard code (IS) for concrete mix design and it has acted as a reference document towards the traditional practice of concrete and has implemented uniformity in the projects. IS forms a strong foundation concerning strength-based mix-design for GPC, but does not focus on activator concentration, binder-to-sand ratios and specific gravity of raw materials, which are essential to evaluate GPC’s functioning. The development of IS to accommodate these parameters, together with standardized curing methods for GPC, would establish a specific mix-design framework to ensure uniform quality and enable large-scale implementation. The guidelines that are currently used are either a derivative of the Portland cement recommendations with minimal modifications or created using empirical and iterative methodologies like the hit-and-trial method, which is known to be very ineffective in reproducibility between different laboratories (Parveen and Singhal, 2017). Although a number of studies suggest some changes in IS code to be applied for GPC, they often do not consider some important variables like activator concentration, Si/Al ratio and the reactivity of a binder, which have a decisive impact on performance (Lahoti et al., 2017). Also, there is currently no known standard where modern computation methods like Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning (AI/ML) are being applied for the prediction of compressive strength, thus restricting their accuracy and experimentation work (Revathi et al., 2024). The widespread use of AI in construction should be primarily a government responsibility, as it accelerates and simplifies communication between all stakeholders (Valery et al., 2023). To address these gaps, it is recommended that national standards be updated to incorporate performance-based and material-specific criteria for geopolymer systems, integrating empirical research on local materials and laboratory validation under various scenarios like fire, chemical attack, etc. Establishing such frameworks would not only enhance structural fire safety but also promote the use of sustainable cementitious materials, supporting both safety and environmental objectives in Indian construction practice (Lahoti et al., 2019).

In addition to mix design, curing conditions play an important role in achieving the desired strength, especially in alkali-activated systems. Contrary to conventional concrete, the latter is typically heat cured through steam or oven curing, speeding the geopolymerization reaction to attain the best mechanical performance of the mix (Rangan, 2014). It has been found that ambient curing alone is not capable of providing the required strength. This confirms the importance of controlled temperature in the early stages of curing (Vijai et al., 2010). It has been found that high temperatures of 60 °C to 100 °C for 24-36 hours can have a substantial enhancement in the compressive strength, particularly in the fly ash-based mixes (Hardjito and Rangan, 2005). Also, introducing chemical additives into concrete, particularly naphthalene sulfonate-based superplasticizers, has been known to enhance efficiency and general performance of the numerous curing processes (Rangan, 2014). Over the past years, significant studies have been conducted regarding means of improving the strength and structure of GPC using supplementary procedures, such as integration of multilayered natural-fiber composite (Mani et al., 2025). GPC made of fly ash, specifically, has been an item of interest because it is both cost-efficient and environmentally friendly. These results can be explained by the large number of reviews pointing to the overall effects of precursor composition, alkali activator concentration and environmental conditions on the properties of geopolymer concrete.

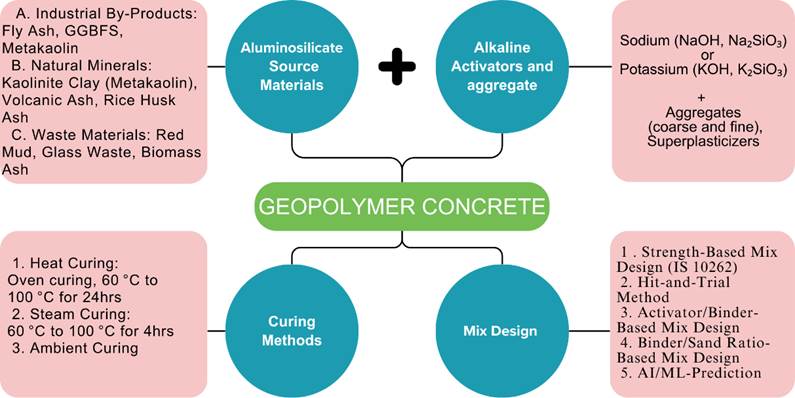

This review paper is devoted to study of the curing processes, as well as IS codes and mix designs, which contribute to the GPC performance. It brings out the basic ideas pertaining to Indian code provisions and their applicability for GPC. The different materials, types of curing, activator solution ratio and tests conducted are discussed, along with their implications on curing needs and strength gains. All the possible codes of IS applicable in this regard have been listed and shown in a consolidated way so as to give a clear and focused reference to researchers and practitioners involved in geopolymer concrete research. Figure 1 suggests a clear description of the major elements and operations that comprise the GPC production process. It points out the key construction materials, curing procedures and mix design patterns.

Fig. 1. Composition, Curing techniques and Different Mix Design Approaches, schematic for GPC

1.1 Need for the study

Nonetheless, the main problem still exists in spite of the developments; that is, the non-standardized curing procedures and design initiatives that relate more specifically to the GPC. Laboratory studies usually use controlled heat curing, but in practice, the weather conditions can cause changes in the properties of concrete and logistical constraints make this impossible to implement other methods of curing. This lack of uniformity affects mass application and restricts its applicability in different construction environments. Although the international standards, such as American Concrete Institute (ACI), British Standards (BS), Standards Australia (AS) and European Standards (Eurocode/EN), are highly regarded and applicable, the IS Codes are specifically developed in such a way that they address local Indian conditions which include, material availability, weather patterns, seismic activity and soil conditions. These codes are required for private/government projects, ensuring they meet national standards and are consistent with local needs. Meanwhile, concreting measures should also be made according to the dynamics of the Indian climate, i.e., from Rajasthan's extreme heat to the Northeast's heavy rains, different regions need specific curing approaches. Improper curing methods may lead to poorer concrete, a higher number of cracks and higher standards of maintenance. The narrative on curing methods and their suitability will guide construction practitioners to make better decisions that balance technical needs with practical and economic realities across India's varied landscapes.

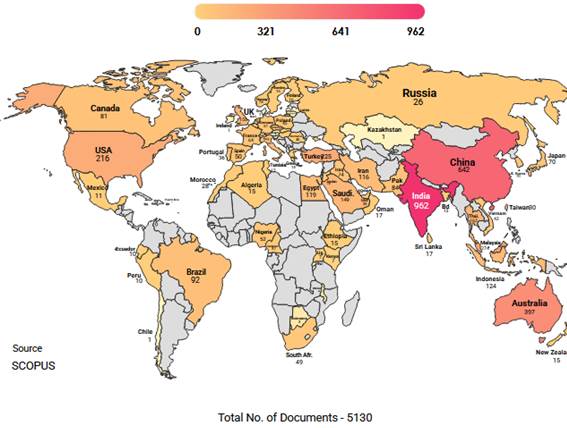

Fig 2. Country-wise leaders in GPC research (Data source: Scopus)

1.2 Two decades of progress: India's geopolymer concrete research Maturity (2007-2024)

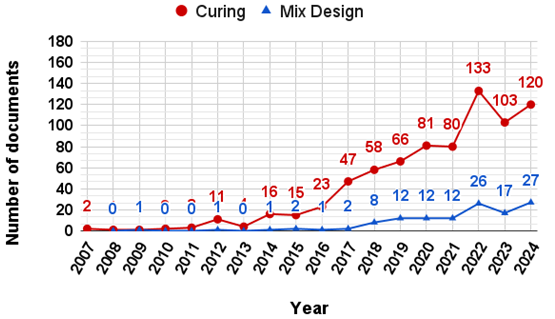

Huge infrastructure demands have driven India and China to conduct the maximum GPC research globally in the design of mixes and in curing practices (Figure 2). The majority of the research originates from Asia and Europe, leaving Africa and smaller countries far behind. Publication trends (Figure 3) in Scopus (2007-2024) reveal India's growing GPC research with 888 papers, reflecting the increased focus on sustainable construction. Data shows that curing research (133 research papers published in 2022 and 120 research papers in 2024) developed at 22.3% annually since 2016, focusing on heat/ambient/steam curing. The mix design studies have grown more rapidly (39% per year), up to 26-27 papers in 2022-2024, as compared with 1-2 papers in 2016, to accommodate the demands of sustainable formulations. These trends show the increasing efforts of India to come up with viable curing options and green mixes in order to render construction sustainability.

Fig 3. Year-wise distribution of Indian research publications (Data source: Scopus)

Overall, it is possible to note that the analysis period (2007-2024) observed the evolution of the Indian research on GPC, which advanced the foundational studies and the optimization at the laboratory level, crossed the threshold of large-scale practice, durability testing, impact on the environment and field implementation, the full characteristics of which are both scientific and industrial. The prominent growth over the last couple of years highlights India's role as a major player in terms of sustainable construction technology in the international scenario (Abdullah et al., 2024).

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Mix Design and Indian Standard (IS) provisions for GPC

Within the GPC mix design, various approaches have been considered to achieve the best performance, ensuring practicability and consistency. One of the approaches is the strength-based mix design given in IS 10262 code applicable to ordinary Portland cement concrete. Anuradha (Anuradha et al., 2012) modified this approach to GPC by correcting some parameters to suit the peculiar behavior of alkali-activated systems by using fly ash and GGBS. Based on the required strength, this method offers a reliable mix design while complying with India's official construction standards. Nevertheless, its versatility is constrained by the complicated chemistry of geopolymerization that cannot be overcome completely based on the principles of the traditional design mix. In another study, fly ash GPC has obtained stable strength gain and workability behavior under the mix design process using IS codes (Patankar et al., 2015).

The hit-and-trial method, on the other hand, has become very common in experimental works, more precisely where one has to work on a fresh material or a combination where it has no established guidelines to follow. Despite its flexibility and responsiveness to various material properties, such an approach is time and resource consuming and tends to bring inconsistencies across the batches and even across the laboratories. To overcome these limits, statistical measures like the Taguchi method have been initiated to streamline the number of experimental tests to be effective. According to a study by Tanakorn P. (Tanakorn P. and Chattarika P., 2018), the design of Taguchi experiments has been successfully implemented in the concrete made of alkali-activated high-calcium fly ash, which allows for determining the most advantageous mixing parameters with the lowest amount of experimental work. Its higher degree of accuracy and reproducibility can be a drawback in comparison with the prevalence of application of the method in everyday building practice, as it requires complex data analysis and specific knowledge.

An upcoming method to follow is alkali solution dosage based on the activator-to-binder ratio mix design approach, where no emphasis is on the volume of alkaline solution since the presence of binder is given equivalent focus. The impact of the concentration of Sodium Hydroxide (NaOH) and the activator-to-fly ash ratio is also presented by Pavitra (Pavithra et al., 2016), under which the researchers emphasized that the desired composition of the mixture in terms of the chosen mechanical properties could be achieved when the appropriate amount of NaOH and the activator-to-fly ash ratio were maintained. The technique also considers chemical reactivity and specific gravity of the raw materials and hence enhances consistency in the mixing. However, it needs well-managed conditions of solution formulation and curing, which may be beyond the field's conditions.

The mix design method based on the binder-to-sand ratio aims at obtaining balanced interactions between the paste and the aggregate so as to ascertain performance and structural integrity. A combination of grading and volume optimization is advocated (Rawat and Pasla, 2024) to maximize packing density in lightweight GPC. Though this method can be used effectively in improving the fresh and hard properties, comprehensive characterization of the aggregate components is needed, which makes the whole formulation process even more complex and costly.

2.2 Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning (AI/ML) Prediction Methods

Optimum mix design and curing conditions of GPC remain complex because of the existence of a nonlinear relationship between factors such as the molar concentration of the activator solution, curing temperature and mixing proportions. Conventional approaches are not effective and this aspect shows the importance of proposing new predictive models (Sobuz et al., 2025). Even though Artificial Neural Network (ANN), Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Interface (ANFIS) and Gene Expression Programming (GEP) based AI/ML models predict the properties of mechanical components successfully (Anwar et al., 2025).They are usually not interpretable to make practical changes in mixes (Sobuz et al., 2025). Combined effects of variables, including the duration of curing and aggregate type, have been largely ignored in many studies (Nazar et al., 2023; Anwar et al., 2025). The recent explainable AI methods, such as SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) and Partial Dependence Plot (PDP) enhance the transparency (Sobuz et al., 2025), but full-scale frameworks that combine predictive accuracy with practical verification are yet to be developed (Anwar et al., 2025). Future work should focus on combining different ML models to optimize GPC mix design and curing processes for sustainable construction. These predictions can then be verified by evaluating the structural performance of the components using advanced numerical modeling, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Advanced Modeling and ML for GPC Validation

|

Model Type |

Purpose / Application |

Key Input Parameters |

Performance / Outcome |

References and Notes |

|

Numerical Modeling (ANSYS FEM) |

Validate structural performance of GPC components (e.g., wall panels) under cyclic loading. |

Geometry, material properties, boundary conditions, loading patterns. |

Accurately simulates cyclic behavior within 10% of experimental data. Enables analysis of load capacity, ductility and stress distribution across openings. |

(Saloma et al., 2023); High-fidelity simulation for design validation. |

|

Machine Learning (ANN, GPR) |

Predict compressive strength of GPC from mix design. |

Binder ratio, activator ratio, curing age. |

Achieves high prediction accuracy with R² > 0.95. Uses k-fold cross-validation for robust lab calibration. |

(Ramujee et al., 2024); Ahmad et al. (2021); Lab-based data-driven modeling. |

|

Ensemble ML (AdaBoost) |

Predict strength for field/variable curing conditions. |

Fly-ash mix proportions, curing parameters. |

Maintains reliable accuracy with RMSE < 3 MPa under variable on-site curing. Enhanced generalization for practical use. |

(Haruna et al., 2025); (Ziolkowski et al., 2021); Suitable for real-world applications. |

The integration of Finite Element Modeling (FEM) with ML creates a robust framework for validating and optimizing geopolymer concrete. FEM provides high-fidelity structural simulation, while ML models offer accurate property predictions. Together, they enable data-driven, efficient design and performance validation for GPC components.

2.3 The Conventional Approach Based on IS Codes

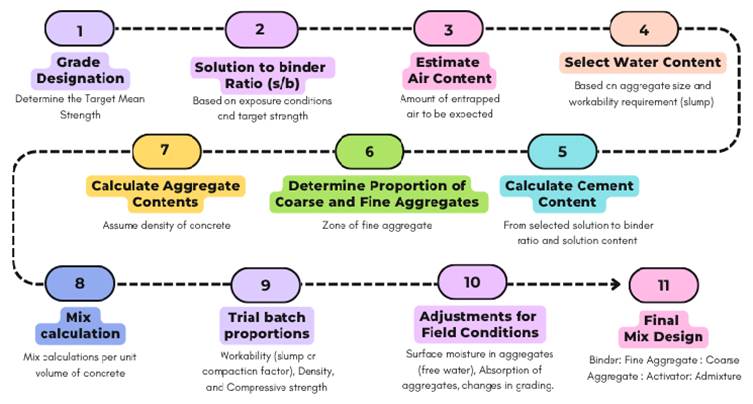

All the mix design methodologies possess unique benefits, such as design based on strength (IS 10262), optimization based on Taguchi method and all face the issue of flexibility, resource consumption and technical practicality. The more integrative approach could be in the hybridization of such approaches, with the effectiveness of statistical modeling being combined with real-world adaptations of the statistics to the properties of materials and constraints of the environment. The protocol should be streamlined to make it simpler so that accuracy is not lost and to gain more widespread use of GPC in sustainable construction industries. Figure 4 shows the systematic procedure for developing mixture proportions of GPC.

Fig 4. Visual guide to GPC mix design steps (Data source: IS 10262:2019)

The classification system presented in Table 2 organizes IS Codes into a structured framework governing concrete technology and construction methods. To assess the properties of fresh concrete, IS 1199 establishes sampling protocols, IS 4031 governs consistency and setting time measurements and IS 7320 governs performance assessment through slump tests. The evaluation of hardened concrete includes IS 516 for compressive and tensile strength analysis, IS 3085 for permeability assessment and IS 13311 for non-destructive testing applications. Material specifications are defined by IS 3812-1 for fly ash quality, IS 16714 for GGBS and IS 383 for aggregate standards, which are supplemented by the IS 2386 (series) for comprehensive aggregate testing. Special construction applications are addressed by IRC 15 for road construction, IS 1343 for prestressed concrete and IS 2770 for reinforcement bond strength.

The Indian construction industry has developed a distinctive approach to mix design by integrating IS 10262 with IS 456, effectively modifying international practices to accommodate local material characteristics and environmental conditions. IS 10262 (IS for Concrete Mix Design) is similar to several international standards, including ACI 211.1, EN 206 and Australian Standard 1379. However, the lack of developed standards for advanced concrete testing poses challenges. Currently, there are no IS equivalents for critical tests such as American Society for Testing and Materials C1202 (ASTM), which measures chloride resistance, ASTM C215-19 used for resonant frequency testing and United States Environmental Protection Agency 1311 (USEPA) for toxicity testing is widely used but not locally adapted. This dependence on foreign standards limits India's ability to independently regulate and innovate in construction materials. Developing a dedicated IS code for these tests will improve quality control, support sustainable construction practices and align India's construction industry with global benchmarks, ultimately strengthening infrastructure development.

Table 2. Comprehensive list of IS codes (Data source: Bureau of Indian Standards (BIS))

|

Parameter |

IS Code |

Standard Title |

|

Workability Flow table Vicat apparatus Slump test Consistency Initial Setting Time Air Permeability Pozzolanic Activity |

IS 1199:2018 IS 5513:1976 IS 7320: 1974 IS 4031 (Part 4) IS 4031 (Part 5) IS 4031 (Part 2) IS 1727:1967 |

Methods of Sampling and Analysis of Concrete Specification for flow table Specification for Vicat apparatus Specification for concrete slump test apparatus Determination of Consistency of Standard Cement Paste Determination of Initial and Final Setting Times Determination of Fineness by Blaine Air Permeability Methods of Test for Pozzolanic Materials |

|

Hardened Concrete Tests |

||

|

Compressive Strength Flexural Strength Split Tensile Strength |

IS 516:1959 |

Methods of Tests for Strength of Concrete |

|

Permeability Non-Destructive Testing (NDT) Bond Strength (Rebar) Durability |

IS 3085:1965 IS 13311 (Part 2):1992 IS 2770 (Part 1):1967 IS 456:2000 |

Permeability of Cement Mortar and Concrete Ultrasonic Pulse Velocity Testing Pull-Out Test for Bond Strength Plain and Reinforced Concrete |

|

Material-specific testing and Design Standards |

||

|

Parameter |

IS Code |

Standard Title |

|

Mix design |

IS 10262:2019 |

Concrete Mix Design (Proportioning Guidelines) |

|

Fly Ash GGBS (Slag) Aggregates |

IS 3812-1 (2003) IS 16714 IS 383:2016 |

Specification for Fly Ash for Use as Pozzolana Specification for Ground Granulated Blast Furnace Slag Coarse and Fine Aggregates for Concrete |

|

Aggregate Tests, Particle Size and Shape, Specific Gravity |

IS 2386 (Series) |

Methods of Test for Aggregates, Gradation Analysis, Physical Mechanical Properties |

|

Natural building stones |

IS 1124: 1974 |

Method of test for determination of water absorption, apparent specific gravity and porosity of natural building stones |

|

Special Applications |

||

|

Application |

IS Code |

Standard Title |

|

Pavements (Roads) Pavement Mix Design Concrete Paving Blocks |

IRC 15:2011 IRC 44:2017 IS 15658: 2021 |

Concrete Roads - Code of Practice Guidelines for Cement Concrete Mix Design for Pavements Concrete Paving Blocks - Specification |

|

Soil Interaction Liquid/Plastic Limits Specific Gravity |

IS 2027 (Series) IS 2027 (Part 5) IS 2027 (Part 3) |

Methods of Test for Soils Soil Consistency Soil Solids |

|

Prestressed Concrete Precast Reinforcement (Steel Bars) Seismic Evaluation Chemical Admixtures Waterproofing Compounds Water/Wastewater Analysis |

IS 1343:2012 IS 18889:2024 IS 1786:2008 IS 15988:2013 IS 9103:1999 IS 2645:2003 IS 3025 (P10):2023 |

Prestressed Concrete - Code of Practice Precast Concrete Paving Flags - Specification High-Strength Deformed Bars Strengthening of RC Buildings Specification for Concrete Admixtures Integral Protection Sampling and Testing |

2.4 Durability and Limitations of IS Codes

GPC has a high freeze-thaw resistance with a loss of less than 1.1% mass after 300 cycles of freezing and thawing in high-calcium mixes with GGBS, which is better than Ordinary Portland Cement (OPC) due to dense Sodium Alumino-Silicate Hydrate (N-A-S-H) and Calcium Alumino-Silicate Hydrate (C-A-S-H) gels that are developed during thermal curing. The sulfate and chloride degradation is low and the chloride penetration 50% less than OPC due to fine pore structures of optimized activator ratios. Indian field exposure confirms sustained performance in humid coastal environment when ambient curing followed by initial heat (Lokesha et al., 2024; B. Zhang, 2024;Amran et al., 2021; P. Zhang et al., 2025:Kanagaraj et al., 2023; Degirmenci, 2018).

The existing IS codes have no GPC-specific mix design guidelines, which makes it necessary to rely on OPC proportions, which do not consider activator molarity, curing regimes and result in an error margin of 20-30% in the final strength. This has been in the form of no requirements made to cover the effects of thermal curing on the workability or durability tests leading to inconsistency in the GPC approvals. The priority revisions are to be standardized in activator ratios, incorporate GPC durability procedures and authenticate against the fly ash variability (Danish et al., 2022; Jeyasehar et al., 2013; Meshram, 2023; Chowdhury et al., 2021; Thirugnanasambandam, 2018).

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Curing Strategies for GPC

The curing is significant in the mechanical and durability properties of GPC and this is a trait that sets GPC apart from the traditional Portland cement systems. A geopolymerization process is a reaction that forms water during the reaction and requires water retention to gain strength (Bagde et al., 2022; Kanagaraj et al., 2022). This subtle distinction necessitates a specific curing regimen and the methods are thermal (60°C-100 °C), ambient curing, steam curing and solar-assisted curing (Davidovits, 2013; Alex et al., 2022). Such compliance of the methods with their influence on the microstructural development of the binder phase is also directly associated with the effectiveness of the methods and indeed, high temperatures tend to favor early strength and ambient temperatures offer slower and more stable growth of strength over time (Vijai et al., 2010).

The heat curing processes, i.e., oven or steam curing process, lead to the formation of a thick network of aluminosilicate gel-matrix, which is essential to attain high compressive strength within a short duration (Hardjito, 2004).Nevertheless, when the heat is too high and the time is too short, free water gets evaporated rapidly, producing microcracks necessitating controlled temperature and time exposure. By contrast, ambient curing does not involve any thermal stress and is more applicable to cast-in-place materials where control of heating is difficult (Shilar et al., 2022). Instead, faster setting periods and superior mechanical properties may be obtained by ambient-cured nano-modified geopolymers, in particular those with nano-silica (Prakasam et al., 2019). The curing effect is also observed past the compressive strength, extending to the fracture energy, tensile property and elastic modulus. It has also been demonstrated that GPC is better at crack resistance, showing greater fracture energy than Portland cement (Nath and Kumar Sarker, 2016). In the meantime, samples cured using heat yield a much higher early strength: this is advantageous when working with precast parts, in which a short production cycle and quick demolding are desirable (Hardjito and Rangan, 2005; Muthuramalingam et al., 2016). Moreover, the aspect of condition curing directly affects long-term durability levels, including water absorption and porosity, with the most fine-tuned regimens leading to lower permeability levels and a longer service life (Kanagaraj et al., 2022).

Concisely, issues like material composition, environmental limitations and expression of desired performance should be taken into consideration when choosing the right curing technique. The choice of heat curing is still the preferred solution when working in precast with a high strength requirement, yet the ambient curing offers a convenient and effective alternative in the field. A balanced comprehension is more vital in these curing approaches to guarantee technical performance and long-term placement of the GPC in the contemporary construction mechanics. Figure 5 shows the advantages and disadvantages of various curing techniques used in GPC, including heat, ambient and steam curing. Each method exhibits different effects on curing time, energy requirements and resulting physical properties. Heat curing accelerates strength development but increases energy consumption, while ambient curing is economical but slow. Steam curing increases efficiency by using less energy, but increases water absorption at a younger age compared to normal curing, although absorption decreases over time in all methods (Hardjito, 2004). Comparative analysis helps in the selection of the most appropriate curing method based on specific application needs.

Fig. 5. Merits and demerits of Curing Method

Table 3. A state-of-the-art assessment on applications related to curing method

|

Ambient |

Steam |

|

|

Commercial: Precast facade panels, Architectural cladding, Sewer pipes (Gourley et al., n.d.) Infrastructure: Railway sleepers, electric poles (Muthuramalingam et al., 2016) Industrial: Factory floors, Prefabricated drainage channels (Seung Yup Yoo, 2014) Precast footway panels (Andrews, 2011) |

Residential: Low-rise buildings, Foundations (Nath and Kumar Sarker, 2016) Commercial: Parking slabs, Walkways (Vijai et al., 2010) Transport: Airport runway repairs, Bus rapid transit (BRT) stations (Glasby et al., 2015) Marine Structures (Rahman and Al-Ameri, 2022) Rural roads (Bellum et al.,2020) |

Infrastructure: Bridge girders, Metro viaducts Marine: Port wharves, Coastal retaining walls (Venkatesan and Pazhani, 2016) Sewer pipeline (Gourley et al., n.d.) Box culverts (Cheema et al., 2009) |

The application of GPC based on curing techniques is shown in Table 3. Heat curing is used in commercial, industrial and transportation sectors, including precast elements and infrastructure. Ambient curing is suitable for residential and rural applications due to its low energy demand. Steam curing is used in infrastructure, industrial and marine projects, which provides increased efficiency. Each method aligns with specific project requirements, highlighting the versatility of GPC in a variety of construction needs. The next sub-section discusses further research on how different binder materials affect curing methods.

3.2 Study of various binder materials’ influence on curing methods

Fly ash is a by-product of coal combustion, primarily from power plants, that is rich in silica and alumina. It originated as a waste but is now used in sustainable GPC. When activated with an alkali solution, it increases the strength and durability of concrete. Curing at 60°C for 24 hours only provides high strength, although after 48 hours, it's less beneficial. Additionally, ambient curing can provide 15% more strength than steam-curing (Hardjito, 2004); (Lloyd and Rangan, 2010).

Similarly, a by-product of iron production, GGBS is a sustainable alternative to Portland cement. Studies show that curing has a significant effect on GGBS-based geopolymers. In a study, El-Hassan (El-Hassan et al., 2017) reported a dense microstructure and low porosity, which increased performance. Karuppannan observed a maximum strength of 21.35 MPa for an 80% GGBS mix cured at 80°C. These results confirm that increased curing temperature accelerates geopolymerization, reduces porosity and significantly improves mechanical properties in GGBS-based systems (Karuppannan et al., 2020).

After this, Alccofine powder, which is made by grinding ultra-fine slag material, has high calcium and silica content, helps GPC set quickly and gain strength. A key advantage is that Alccofine concrete cures at room temperature, unlike regular GPC, which requires heat, making it easier in construction (Goyal et al., 2019). Heating at 80°C accelerates geopolymerization and improves the performance of Alccofine and calcined clay. However, this heat can cause cracks when using aluminum powder in porous structures (Kumar et al., 2019).

Similarly, rocks containing gold are mined. After crushing and processing this rock, the remaining sand-like material is called tailings. These tailings are obtained from gold mines like Kolar Gold Fields (India) and Nova Scotia (Canada) (Preethi A, 2017). Studies have shown that gold ore tailings in GPC can be cured at ambient temperature. Although they contain harmful metals, geopolymerization traps these metals, making the GPC safe in construction (Lokesha et al., 2024).

Further, kaolin is formed when feldspar rocks break down under warm, moist, or acidic conditions. First discovered in Gaoling, China, it is now mined in China, the United States, India and Brazil. As the weathering happens, they change from halloysite to kaolinite (Ali Sayin, 2007). Similarly, volcanic ash can replace part of the cement, providing strength comparable to traditional concrete (Susanti et al., 2018). Kaolin and fly ash-based GPC, heat curing at 100°C for 72 hours, gives the strongest results. Mixing kaolin with fly ash and silica fume helps in producing durable concrete (Okoye et al., 2015).

Furthermore, silica fume is a very fine powder produced during the manufacturing of silicon and ferrosilicon alloys in an electric arc furnace. Once considered waste, this fume has been used in concrete since the 1970s. Its small particles make concrete stronger and water-resistant. (Siddiqi et al., 2023). Steam curing works best for early strength, which makes the concrete denser. Adding 2% silica fume gives the best strength increase, but beyond this value, it does not increase strength (Nagarajan A, 2022).

In the same context, Rice Husk Ash (RHA) comes from the burning of rice husks, an agricultural by-product. It is rich in silica and is primarily collected from rice-growing areas. Its quality depends on how it is burned, with the best silica content at a certain temperature. RHA helps make concrete stronger and durable (Okoya B.A 2021). Heat curing improves its durability and corrosion resistance. RHA creates a dense, protective structure that performs particularly well when heat-cured, allowing it to last longer in severe conditions. (Indrajit Krishnan and Nagan, 2025)

Similarly, nano silica comes from nature (like rice husk ash) and from man-made processes. It's made by using chemical methods (sol-gel, flame pyrolysis) and eco-friendly sources include sugarcane waste (Uniyal et al., 2025). Adding nano silica to Fly ash/GGBS geopolymer mortar helps it cure at room temperature, making it durable and fracture-resistant for critical construction. (Prakasham et al., 2020)

Finally, metakaolin is made by heating kaolin clay (650-750°C), converting it into a reactive powder. Found worldwide, it improves the strength and durability of concrete (Ibrahim et al., 2018). Oven curing gives better initial strength, while high temperature can weaken it. Proper curing ensures optimal performance (Shilar et al., 2022).

Table 4 presents a compilation of Indian research studies investigating particularly the curing and material characteristics of GPC. Studies have shown that steam curing significantly increases compressive strength, fracture resistance and chloride ion resistance compared to ambient curing. For example, samples cured under steam at 60°C for 24 hours show higher compressive and tensile strengths compared to ambient curing (Nagarajan A, 2022). The implementation of activators NaOH, KOH and Na₂SiO₃ in various molarities and proportions has an impact on the process of geopolymerization, which influences the subsequent performance of such a material (Kumar et al., 2019; Lokesha et al., 2024; Ding et al., 2018). Improvement in mechanical properties is also achieved due to high molarity and optimal solution to binder ratio, as evidenced by compressive strength, flexural strength and modulus of elasticity (Girish et al., 2025; Vora and Dave, 2013; Okoye et al., 2015; Indrajith and Nagan, 2025). High temperature curing, especially 60°C - 90°C, increases the rate of reaction and thus, the strength is achieved quickly and porosity is low (Vora and Dave, 2013; Muthuramalingam et al., 2016). Moreover, nano-silica, graphene oxide and silica fume as additives can be included to improve the microstructure and durability of GPC (Prakasam et al., 2020; Bellum et al., 2020). All in all, to come up with good performance geopolymer materials that provide sustainable and long-lasting substitutes to normal concrete, there must be an enhanced condition of curing.

Table 4. Indian Research on GPC Curing Properties

|

Sr. No. |

Title |

Author |

Aluminosilicate Sources |

Activator Ratio (Na2SiO3 / NaOH) |

Molarity |

S/B Ratio* |

Curing Method |

Summary |

|

1 |

Influence of some additives on the properties of fly ash based geopolymer cement mortars |

(Kumar et al., 2019) |

Fly Ash (FA), Alccofine Powder, Aluminum Powder and Calcined Clay |

NaOH, Potassium hydroxide (KOH), Na2SiO3 and Lithium silicate (Li2SiO3) |

8, 10, 12 and 14 M |

- |

80°C Oven |

FA geopolymer mortar formulations require optimized activator ratios and additives. |

|

2 |

Durability characteristics of geopolymer concrete produced using gold ore tailings along with recycled coarse aggregates |

(Lokesha et al., 2024) |

Gold Ore Tailings, Class FA, GGBS |

NaOH and Na2SiO3 |

14M |

- |

Ambient |

Demonstrated increased resistance to alkaline and acidic environments. |

|

3 |

Fracture properties of slag/fly ash-based geopolymer concrete cured in ambient temperature. |

(Ding et al., 2018) |

FA, GGBS |

2.5 |

14M |

0.35 and 0.4 |

Ambient |

The surrounding GPC improves fracture properties along with compressive strength. |

|

4 |

Effect of Slag Sand on Mechanical Strengths and Fatigue Performance of paving grade geopolymer concrete |

(Girish et al., 2023) |

FA, GGBS |

1:2.5 |

10M |

0.45 |

Ambient 7, 14, 28 and 56 days. |

Curing without water, rapid reopening for road traffic and excellent fatigue resistance under cyclic loading are key advantages. |

|

5 |

Parametric Studies on Compressive Strength of Geopolymer Concrete |

(Vora and Dave, 2013) |

FA |

2 and 2.5 |

14M |

0.35 and 0.4 |

48 hours at 75°C |

The CS of the GPC increases with an increase in the curing time. However, the increase in strength beyond 24 hours is not very significant. |

|

6 |

Fly ash/Kaolin based geopolymer green concretes |

(Okoye et al., 2015) |

FA, Kaolin, Silica Fume |

KOH 2.5 |

14M |

- |

40°C to 120°C |

- |

|

7 |

Electrochemical assessment of rebar corrosion resistance in geopolymer concrete incorporating ground granulated blast furnace slag and rice husk ash |

(Indrajith Krishnan and Nagan, 2025) |

Rice Husk Ash (RHA) and GGBS |

2.5 |

12 M |

0.5 |

60°C Oven |

Thermally-treated samples are better than ambient-cured samples in chloride resistance and anti-corrosion performance. |

|

8 |

Effect of red mud-based geopolymer binder on the strength development of clayey soil |

(Singh et al., 2023) |

Red Mud and Bauxite Tailings |

2.3 |

5M |

- |

Ambient |

Red mud shows potential as a geopolymer binder for soil stabilization applications. |

|

9 |

Mechanical properties of geopolymers synthesized from fly ash and red mud under ambient conditions |

(Nevin K., 2019) |

FA and Red Mud |

Sodium metasilicate pentahydrate (Na2SiO3 ·5H2O) 2.5 |

weight-to-weight ratios |

- |

Ambient |

Hardness increases with curing time, from ductile to brittle at high fly ash content. |

|

10 |

Strength and durability properties of geopolymer concrete made with ground granulated blast furnace slag and black rice husk ash |

(Venkatesan and Pazhani, 2015) |

GGBS and Black RHA |

2.5 |

8M |

0.4 |

Ambient, 60°C and 90°C for 8 h |

Oven-cured samples achieved higher compressive strength compared to their ambient-cured counterparts. |

|

11 |

Mechanical, durability and fracture properties of nano-modified Flyash/GGBS geopolymer mortar |

(Prakasam et al., 2019) |

FA, GGBS and Nano Silica |

2.06 |

3M |

0.3 |

Ambient |

Nano-silica promotes geopolymerization, producing more sodium aluminosilicate hydrate (Al₂H₂Na₂O₇Si) and reducing matrix porosity. |

|

12 |

Behaviour of ambient cured prestressed and non-prestressed geopolymer concrete beams |

(Sonal et al., 2022) |

FA, GGBS |

2.5 |

14M |

- |

Ambient |

Atmospherically cured prestressed GPC beams match the load capacity of Portland concrete with sufficient strength. |

|

13 |

Development of high-strength geopolymer concrete in corporating high-volume copper slag and micro silica |

(Nagarajan A, 2022) |

FA, Copper Slag and Silica Fume |

2.5 |

12M |

- |

Ambient and Steam curing 60°C 24 h |

The compressive and tensile strengths of samples cured under ambient conditions were significantly lower than those of steam-cured samples. |

|

14 |

Investigation on performance enhancement of fly ash-GGBS based graphene geopolymer concrete |

(Bellum, et al., 2020) |

FA, GGBS |

Na2SiO3 / NaOH and Graphene oxide 2 |

8M |

0.4 |

Ambient 28 and 60 days |

Demonstrated increased compressive strength and elastic modulus |

|

15 |

Behavioural analysis of fly ash based prestressed geopolymer concrete electric poles |

(Muthuramalingam et al., 2016) |

FA |

2.5 |

16M |

0.48 |

90°C 24h Oven |

The developed GPC showed improved performance and superior mechanical properties compared to conventional concrete. |

|

16 |

Evaluation of structural performances of Metakaolin based geopolymer concrete |

(Shilar et al., 2022) |

Marble Powder and Metakaolin |

Potassium silicate (K₂SiO₃) and (KOH) |

14M |

0.25 - 0.50 |

50°C for 7, 14, 28 and 90 days. |

Potassium-activated GPC exhibits significantly superior strength properties compared to conventional concrete. |

|

17 |

Development of various curing effect of nominal strength Geopolymer concrete |

(Kumaravel, 2014) |

FA, GGBS |

2.5 |

8M |

- |

Steam and hot air at 60°C and Ambient |

Heat-cured concrete exhibits significantly higher compressive strength than atmospherically cured specimens. |

|

|

||||||||

3.3 Economic Viability, Sustainability and Policy Recommendations

GPC mix designs using Indian fly ash and GGBS have an initial cost of materials 10-22% higher than that of OPC because of the expenses of the activators, but the life cycle cost decreases by 13% over 50 years due to lower maintenance. Cradle-to-gate Life Cycle Analysis (LCA) demonstrates reduction of 60-80% of CO2 emissions, which is caused by use of industrial waste (binder), but some obstacles are involved, such as poor quality of precursors and high up-front costs. A metakaolin‑based geopolymer mixture achieved a 61% reduction in global warming potential relative to the cement concrete. Pilot projects in India indicate that precast elements are economically viable at large-scale production when the cost of activator and logistics is decreased by scaling. (Munir et al., 2023; Aafsha Kansal et al., 2022; Kiruthika K et al., 2023; Tamoor & Zhang, 2025; Omid B & Amir M R, 2025; Das et al., 2022). Table 5 lists the estimated material cost for geopolymer concrete in India. Table 6 provides a life cycle comparison between geopolymer concrete and OPC in the Indian context.

Table 5. Rate comparison for GPC and OPC for Indian Scenario in Indian rupee (INR) per m³

|

Component |

Typical Quantity (M25/M30 Grade) |

Cost Contribution (INR) |

Notes |

|

Fly Ash/GGBS |

400-500 kg (FA50%-GGBS50%) |

Low INR. 0.44/kg fly ash) |

Waste-derived binder |

|

Sodium Silicate |

60 kg |

900 |

High activator cost |

|

NaOH Pellets |

20 kg |

2,400 |

Dominant expense |

|

Aggregates |

1,200-1,500 kg |

Similar to OPC (~1,500) |

Standard |

|

GPC M25/M30 |

- |

4,699/ 5,883.5 |

27% higher than M25 OPC (INR 3,675) |

|

OPC M25/M30 |

- |

3,675 / 5,780 |

Standard rates |

Table 6. LCA comparison for GPC and OPC

|

Impact Category |

Geopolymer Concrete |

OPC Concrete |

Reduction |

|

CO₂ Emissions |

80% lower (fly ash full/partial) |

Standard rates |

No clinkering |

|

Global Warming Pot. |

Superior |

Higher |

Waste utilization |

|

Energy Use |

Lower embodied (bulk scale) |

Higher |

Up to 40% cost parity |

|

Durability |

High thermal stability (800°C) |

Standard |

Ambient/heat curing |

Geopolymer concrete in India leverages abundant fly ash from thermal plants, achieving 27% higher initial material costs (INR 4,699/m³ vs. INR 3,675 for M25 OPC) due to activators like NaOH and sodium silicate. Optimized mixes with 50% FA-50% GGBS match M25 strength at 28 days, with heat curing at 60-90°C essential for low-calcium fly ash but adding energy; ambient curing viable with slag additions up to 30-40%. LCA reveals 80% CO₂ cuts and potential 10-30% cheaper production long-term via waste streams, especially under pollution taxes, though full fly ash mixes limit ambient strength without additives (Patel et al., 2022, Thaarrini et al., 2016, Verma, et al., 2022; Jeyasehar et al., 2013; Thirugnanasambandam, 2018; Kanagaraj et al., 2023; Rajalakshmi, et al., 2023).

GPC lowers one tonne CO2 per m3 of cement emissions in India by utilizing fly ash as much as possible through policy incentives such as extensions of the Perform, Achieve and Trade (PAT) scheme, which refers to the expansion of India's energy efficiency program under the Bureau of Energy Efficiency (BEE). Suggestions comprise 20% GST rebates on activators, mandatory 10% GPC on public precast like railway sleepers, as well as BIS fast-tracking of IS standards on mix design and curing. Research and development subsidies to Artificial Intelligence-Life Cycle Assessment (AI-LCA) tools can be used to favor low article processing charged journals to Indian researchers. (Aafsha Kansal et al., 2022; Ramesh et al., 2025; Marinelli & Janardhanan, 2022; Strategic Market Research, 2024; Riya Desai, 2025). Conventional OPC production is energy consuming and a source of high CO2 emission per tonne of cement, a motivation for GPC, although the reported studies lack a complete and directly comparable table of process energy (kilowatt hours per m3) of GPC versus OPC (Verma et al., 2022).

4 Conclusions

Although IS 10262 (2019) serves as the reference for GPC in India, a new standard that focuses solely on the alkali activation mechanism, mix design, curing methods, material classification and other technical parameters must be developed, with references to international standards relevant to GPC. More sophisticated approaches, such as the Taguchi optimization or AI/ ML tools, have potential but would need more validation in the field. GPC offers up to 80% CO₂ reduction and 13% lower life-cycle costs, though initial costs remain 20–30% higher due to activators. In curing, the use of heat/steam is still the best way to cure precast elements that require quick strength development, though ambient/air curing with the use of nano-additives has been rising in popularity on-site projects because it uses less energy. To achieve a balance between performance and sustainability, a hybrid curing (short-duration heat curing followed by ambient conditions) method is suggested. GPC shows superior durability but lacks clear IS code standards. Just as government initiatives promote sustainable technologies, such as subsidies for electric vehicles, Incentives for the adoption of urban solar energy and mandates for rainwater harvesting systems in residential complexes, GPC also requires institutional support. AI-based mix optimization and policy incentives like tax rebates and GPC mandates can boost large-scale adoption in India. Government agencies should incorporate GPC into public infrastructure policies, while NGOs can facilitate its adoption through awareness campaigns and demonstration projects. Although GPC cannot yet completely replace cement, it can start with small applications such as rural roads, insulation walls, pavements, pool linings, precast bricks and drainage covers. It will effectively demonstrate its effectiveness and encourage widespread adoption in sustainable construction. The studies in the future should use data not only from Scopus but also from Web of Science and fill major gaps like the cost of materials, long-term durability and large-scale production. Important parameters such as molarity, fly-ash-to-activator ratios, acid resistance and self-healing behave systematically and must be studied to minimize the use of regular concrete. Essential joint efforts shall be initiated between the researchers, policy makers and the industries for awareness, standardization, large-scale implementation, ensuring availability of GPC, the cost reduction and technical challenges shall be addressed to meet the requirements in the Indian construction industry.

Acknowledgements

We thank Department of Civil Engineering, Symbiosis Institute of Technology (SIT), Pune, Symbiosis International (Deemed University) and Pune Construction Engineering Research Foundation (PCERF), Pune, for providing infrastructure and financial support to conduct the research. We appreciate their expert technical guidance and continuous encouragement.

References

- ACI 211.1 American Concrete Institute -Standard Practice for Selecting Proportions for Normal, Heavyweight and Mass Concrete.

- Ahmad, A., Ahmad, W., Chaiyasarn, K., Ostrowski, K. A., Aslam, F., Zajdel, P., & Joyklad, P. (2021). Prediction of geopolymer concrete compressive strength using novel machine learning algorithms. Polymers, 13(19). https://doi.org/10.3390/polym13193389

- Abdullah, A. F., Abdul-Rahman, M. B. A. D., & Al-Attar, A. A. (2024). A review on geopolymer concrete behaviour under elevated temperature influence. Journal of Sustainability Science and Management, 19(12), 239–259. https://doi.org/10.46754/jssm.2024.12.014

- Aafsha Kansal, Shirish Bhardwaj, D. T., & Tarun Garg. (2022). Decarbonizing India’s Building Construction through Cement Demand Optimization: Technology and Policy Roadmap. https://www.aceee.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/ssi21/panel-4/Kansal.pdf

- Alaneme, G. U., Olonade, K. A., Esenogho, E., Lawan, M. M., & Dintwa, E. (2024). Artificial intelligence prediction of the mechanical properties of banana peel-ash and bagasse blended geopolymer concrete. Scientific Reports 2024 14:1, 14(1), 26151-. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-77144-9

- Alex, A. G., Gebrehiwet Tewele, T., Kemal, Z., & Subramanian, R. B. (2022). Flexural Behaviour of Low-Calcium Fly Ash-Based Geopolymer Reinforced Concrete Beam. International Journal of Concrete Structures and Materials, 16(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40069-022-00531-x

- Ali Sayin. (2007). Origin of Kaolin Deposits. In Turkish Journal of Earth Sciences (Vol. 16, Issue 1).

- Andrews-Phaedonos VicRoads, F. (2011). Geopolymer “Green” Concrete-Reducing the Carbon Footprint-The VicRoads Experience. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Geopolymer-%22green%22-concrete%3A-reducing-the-carbon-AndrewsPhaedonos/4aedb6ca4024b2d5954dda2cf6c74673eda7e72e

- Anwar, M. K., Qurashi, M. A., Zhu, X., Shah, S. A. R., & Siddiq, M. U. (2025). A comparative performance analysis of machine learning models for compressive strength prediction in fly ash-based geopolymers concrete using reference data. Case Studies in Construction Materials, 22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2025.e04207

- Anuradha, R., Sreevidya, V., Venkatasubramani, R., & Rangan, B. V. (2012). Modified guidelines for geopolymer concrete mix design using Indian standard. In Asian Journal of Civil Engineering (Building and Housing (Vol. 13, Issue 3). www.SID.ir

- Antony Jeyasehar, M. Salahuddin, Thirugnanasambandam (2013) Development Of Fly Ash Based Geopolymer Concrete Precast Elements, https://moef.gov.in/uploads/2017/08/Geopolymer_MoEF_Project.pdf

- Amran, M., Al-Fakih, A., Chu, S. H., Fediuk, R., Haruna, S., Azevedo, A., & Vatin, N. (2021). Long-term durability properties of geopolymer concrete: An in-depth review. Case Studies in Construction Materials, 15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2021.e00661

- ASTM C1202 (1991) Standard test method for electrical indication of concretes ability to resist chloride ion penetration

- ASTM C215-19 Standard Test Method for Fundamental Transverse, Longitudinal and Torsional Resonant Frequencies of Concrete Specimens

- AS 1379 (2007) (Australian Standard)-Specification and supply of concrete

- Bagde, A., Jamgade, A., Kalambe, D., Ghaiwat, A., & Gajghate Sir, V. (2022). Geopolymer: The Concrete of The Next Decade. www.ijert.org

- Bellum, R. R., Muniraj, K., Indukuri, C. S. R., & Madduru, S. R. C. (2020). Investigation on Performance Enhancement of Fly ash-GGBFS Based Graphene Geopolymer Concrete. Journal of Building Engineering, 32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2020.101659

- Cheema, D., N.A. Lioyd, V.B. Rangan(2009). Durability of geopolymer concrete box culverts-a green alternative http://cipremier.com/100034010www.cipremier.com

- Barrack Omondi Okoya, Sylvester O. Abuodha, Dr. Siphila W. Mumenya, Dr. Simeon O. Dulo, (2021) Characteristics of Kenyan Rice Husk Ash Produced Under Controlled Burning. (n.d.). www.ijert.org

- Chowdhury, S., Mohapatra, S., Gaur, A., Dwivedi, G., & Soni, A. (2021). Study of various properties of geopolymer concrete – A review. Materials Today: Proceedings, 46, 5687–5695. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.MATPR.2020.09.835

- Davidovits, J. (1990). Geopolymeric concretes for environmental protection. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/292545984

- Davidovits, J. (1993). Geopolymer cement to minimize carbon dioxide greenhouse-warming. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/284682578

- Davidovits, J. (2013). GEOPOLYMER CEMENT. www.geopolymer.org

- Danish, A., Ozbakkaloglu, T., Ali Mosaberpanah, M., Salim, M. U., Bayram, M., Yeon, J. H., & Jafar, K. (2022). Sustainability benefits and commercialization challenges and strategies of geopolymer concrete: A review. Journal of Building Engineering, 58, 105005. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JOBE.2022.105005

- Degirmenci, F. N. (2018). Freeze-thaw and fire resistance of geopolymer mortar based on natural and waste pozzolans. Ceramics-Silikáty, 62(1), 41–49. https://doi.org/10.13168/cs.2017.0043

- Ding, Y., Shi, C. J., & Li, N. (2018). Fracture properties of slag/fly ash-based geopolymer concrete cured in ambient temperature. Construction and Building Materials, 190, 787–795. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.09.138

- El-Hassan, H., Ismail, N., Al Hinaii, S., Alshehhi, A., & Al Ashkar, N. (2017). Effect of GGBS and curing temperature on microstructure characteristics of lightweight geopolymer concrete. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/319014900

- EN 206 (European Standard) Concrete. Specification, performance, production and conformity.

- Girish, M. G., Shetty, K. K., & Nayak, G. (2023). Effect of Slag Sand on Mechanical Strengths and Fatigue Performance of Paving Grade Geopolymer Concrete. International Journal of Pavement Research and Technology, 18(3), 543–560. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42947-023-00363-2

- Glasby, T., Day, J., Genrich, R., Aldred, J., & Manager, E. (2015). EFC Geopolymer Concrete Aircraft Pavements at Brisbane West Wellcamp Airport. https://www.wagner.com.au/media/1512/bwwa-efc-pavements_2015.pdf

- Gourley, T., Alliance, G., & Johnson, G. (n.d.). The Corrosion Resistance of Geopolymer Concrete Sewer Pipe. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/336639705

- Goyal, P., Zail Singh, G., & Kumar Singla, R. (2019). Experimental study: Alccofine as strength enhancer for geopolymer concrete. In International Journal of Advance Research. www.IJARIIT.com

- Hardjito, D., & Rangan, B. V. (2005). Development and Properties of Low-Calcium Fly Ash-Based Geopolymer Concrete. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228794879

- Hardjito, D. (2004). On the Development of FlyAsh-based Geopolymer Concrete. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/303836414

- Haruna, S. I., Ibrahim, Y. E., & Abba, S. I. (2025). Machine learning algorithm for predicting the compressive strength of sustainable ultra-high-performance concrete (UHPC) containing supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs). Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering. https://doi.org/10.1080/13467581.2025.2585646

- Ian Tiseo. (2025). Global and India cement CO₂ emissions 1960-2023. Statista, Global Carbon Project. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1299532/carbon-dioxide-emissions-worldwide-cement

- Ibrahim, S. S., Hagrass, A. A., Boulos, T. R., Youssef, S. I., El-Hossiny, F. I., & Moharam, M. R. (2018). Metakaolin as an Active Pozzolan for Cement That Improves Its Properties and Reduces Its Pollution Hazard. Journal of Minerals and Materials Characterization and Engineering, 06(01), 86–104. https://doi.org/10.4236/jmmce.2018.61008

- Indrajith Krishnan, R., & Nagan, S. (2025). Electrochemical assessment of rebar corrosion resistance in geopolymer concrete incorporating ground granulated blast furnace slag and rice husk ash. Ceramics - Silikaty, 69(3), 321–333. https://doi.org/10.13168/cs.2025.0016.

- IRC 15 (2011). Standard specifications and code of practice for the construction of concrete roads, BIS New Delhi, India.

- IRC 44 (2017) Guidelines for cement concrete mix design for pavements, BIS New Delhi, India.

- IS 1199: 2018 Part 2-1 Fresh concrete- methods of sampling, testing and analysis.

- IS 10262: 2019 Concrete mix proportion guidelines, BIS New Delhi, India.

- IS 456: 2000 Plain and reinforced concrete - code of practice, BIS New Delhi, India.

- IS 5512: 1983 Specification for flow table for use in tests of hydraulic cements and pozzolanic materials, BIS New Delhi, India.

- IS 7320: 1974 Specification for concrete slump test apparatus, BIS New Delhi, India.

- IS:4031 Part 4 Methods of physical tests for hydraulic cement, Determination of consistency of standard cement paste, Part 5- Determination of initial and final setting time, Part-2 Determination of fineness by specific surface by the Blaine air permeability method, BIS New Delhi, India.

- IS 1727:1967 Methods of test for pozzolanic materials, BIS New Delhi, India.

- IS 516:1959, Methods of Tests for Strength of Concrete, Bureau of Indian Standards (BIS) New Delhi, India.

- IS 3085:1965 (Reaffirmed Year: 2021) Method of Test for Permeability of Cement Mortar and Concrete, BIS New Delhi, India.

- IS 13311 (Part 2):1992 – Non-Destructive Testing of Concrete – Methods of Test, BIS New Delhi, India.

- IS 2770 Part 1:1967 Methods of testing bond in reinforced concrete Pull-out test, BIS New Delhi, India.

- IS 3812-1:2003 For Use as Pozzolana in Cement, Cement Mortar and Concrete, BIS New Delhi, India.

- IS 16714: 2018 Ground Granulated Blast Furnace Slag for Use in Cement, BIS New Delhi, India.

- IS 383: 2016 Coarse and fine aggregate for concrete, BIS New Delhi, India.

- IS 2386:1963 Methods of Test for Aggregates for Concrete, BIS New Delhi, India.

- IS 1343:2012 Prestressed Concrete - Code of Practice, BIS New Delhi, India.

- IS 18889: 2024 Precast Concrete Paving Flags – Specification, BIS New Delhi, India.

- IS 2027 Methods of test for soil, BIS New Delhi, India.

- IS 15988: 2013 Seismic Evaluation and Strengthening of Existing Reinforced Concrete Building — Guidelines, BIS New Delhi, India.

- IS 9103: 1999 Specification for Concrete Admixtures

- IS 2645: 2003 Integral Waterproofing Compounds for Cement Mortar and Concrete -Specification, BIS New Delhi, India.

- IS 1786: 2008 High strength deformed steel bars and wires for concrete reinforcement, BIS New Delhi, India.

- IS 3025: Part 10: 2023 Methods of Sampling and Test (Physical and Chemical) for Water and Wastewater, BIS New Delhi, India.

- IS 15658: 2021 Concrete Paving Blocks – Specification, BIS New Delhi, India.

- IS 1124: 1974 Method of test for determination of water absorption, apparent specific gravity and porosity of natural building stones, BIS New Delhi, India.

- IS 5513:1976 Specification for Vicat apparatus, BIS New Delhi, India.

- Kanagaraj, B., Anand, N., Raj R, S., & Lubloy, E. (2022). Performance evaluation of sodium silicate waste as a replacement for conventional sand in geopolymer concrete. Journal of Cleaner Production, 375. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.134172

- Kanagaraj, B., Anand, N., Andrushia, D., & Kodur, V. (2023). Residual Properties of Geopolymer Concrete for Post-Fire Evaluation of Structures. Materials, 16(17), 6065. https://doi.org/10.3390/MA16176065

- Karuppannan, M. S., Palanisamy, C., Farook, M. S. M., & Natarajan, M. (2020). Study on fly ash and GGBS based oven cured geopolymer concrete. AIP Conference Proceedings, 2240. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0011023

- Kiruthika K., Ambily P.S., Ponmalar V. & Senthil Kumar Kaliyavaradhan, Computation of embodied energy and carbon footprint of geopolymer concrete. European Journal of Environmental and Civil Engineering (2023). https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/19648189.2023.2260865tandfonline

- Kumaravel, S. (2014). Development of various curing effect of nominal strength Geopolymer concrete. Journal of Engineering Science and Technology Review, 7(1), 116–119. https://doi.org/10.25103/jestr.071.19

- Kumar, M., Saxena, S. K., & Singh, N. B. (2019). Influence of some additives on the properties of fly ash-based geopolymer cement mortars. SN Applied Sciences, 1(5).https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-019-0506-4

- Lahoti, M., Narang, P., Tan, K. H., & Yang, E. H. (2017). Mix design factors and strength prediction of metakaolin-based geopolymer. Ceramics International, 43(14), 11433–11441. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2017.06.006

- Lahoti, M., Tan, K. H., & Yang, E. H. (2019). A critical review of geopolymer properties for structural fire-resistance applications. In Construction and Building Materials (Vol. 221, pp. 514–526). Elsevier Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.06.076

- Lloyd, N. A., & Rangan, B. V. (2010). Geopolymer Concrete with Fly Ash. http://www.claisse.info/Proceedings.htm

- Lokesha, E. B., Aruna, M., & Reddy, S. K. (2024). Durability Characteristics of Geopolymer Concrete Produced Using Gold Ore Tailings Along with Recycled Coarse Aggregates. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-3850399/v1

- Marinelli, M., & Janardhanan, M. (2022). Green cement production in India: prioritization and alleviation of barriers using the best–worst method. Environmental Science and Pollution Research International, 29(42), 63988. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11356-022-20217-X

- Mani, S., Partheeban, P., & Gifta, C. C. (2025). A comprehensive review on multilayered natural-fibre composite reinforcement in geopolymer concrete. In Cleaner Materials (Vol. 16). Elsevier Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clema.2025.100310

- Meshram, A. (2023). Optimizing and Predicting Compressive Strength of One-Part Geopolymer Concrete. International Journal for Research in Applied Science and Engineering Technology, 11(5), 7457–7472. https://doi.org/10.22214/IJRASET.2023.53436

- S.Thirugnanasambandam. (2018) Development of Fly Ash Based Geopolymer Concrete and Testing of Elements. Annamalai University UGC Project (n.d.). https://annamalaiuniversity.ac.in/download/ugc%20project/UGC%20-%20Major%20Research%20Project%20%20-%20Development%20of%20Geopolymer.pdf

- Muthuramalingam, S., Thenmozhi, R., Vadivel, T. S., & Padmapriya, V. (2016a). Behavioural Analysis of Fly Ash Based Prestressed Geopolymer Concrete Electric Poles Senthil Vadivel Thiyagarajan Manav Rachna Educational Institutions. Middle-East Journal of Scientific Research, 24(7), 2247–2251. https://doi.org/10.5829/idosi.mejsr.2016.24.07.23697

- Mishchenko Valery, Semenov Alexey, Bredikhina Natalia, Bredikhin Aleksandr, (2023), Experience In The Use Of Artificial Intelligence In Making Managerial Decisions In The Construction Of Real Estate, Journal of Applied Engineering Science https://www.aseestant.ceon.rs/index.php/jaes/article/view/42295

- Nagarajan A, J. M. M. C. G. M. N. I. V. (2022). Development of High-Strength Geopolymer Concrete Incorporating High-Volume Copper Slag and Micro Silica. https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/14/13/7601

- Nath, P., & Kumar Sarker, P. (2016). Fracture properties of geopolymer concrete cured in ambient temperature (Issue 7). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/272170672

- Nazar, S., Yang, J., Amin, M. N., Khan, K., Ashraf, M., Aslam, F., Javed, M. F., & Eldin, S. M. (2023). Machine learning interpretable-prediction models to evaluate the slump and strength of fly ash-based geopolymer. Journal of Materials Research and Technology, 24, 100–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2023.02.180

- Nevin K., K. D. L. H. Q. W. J. N. M. (2019). Mechanical properties of geopolymers synthesized from fly ash and red mud under ambient conditions. https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4352/9/11/572

- Omid Bamshad & Amir Mohammad Ramezanianpour (2025) Evaluating geopolymer concrete viability: Cradle-to-cradle life cycle assessment. Environment, Development and Sustainability. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10668-025-06916-8link-springer-com.remotlog

- Okoye, F. N., Durgaprasad, J., & Singh, N. B. (2015). Mechanical properties of alkali activated fly ash/Kaolin based geopolymer concrete. Construction and Building Materials, 98, 685–691. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2015.08.009

- Patankar, S. V., Ghugal, Y. M., & Jamkar, S. S. (2015). Mix design of fly ash based geopolymer concrete. In Advances in Structural Engineering: Materials, Volume Three (pp. 1619–1634). Springer India. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-81-322-2187-6_123

- Pavithra, P., Srinivasula Reddy, M., Dinakar, P., Hanumantha Rao, B., Satpathy, B. K., & Mohanty, A. N. (2016). A mix design procedure for geopolymer concrete with fly ash. Journal of Cleaner Production, 133, 117–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.05.041

- Prakasam, G., Murthy, A. R., & Saffiq Reheman, M. (2020). Mechanical, durability and fracture properties of nano-modified FA/GGBS geopolymer mortar. Magazine of Concrete Research, 72(4), 207–216. https://doi.org/10.1680/jmacr.18.00059

- Parveen, & Singhal, D. (2017). Development of mix design method for geopolymer concrete. Advances in Concrete Construction, 5(4), 377–390. https://doi.org/10.12989/acc.2017.5.4.377Preethi A. (2017). Studies on Gold Ore Tailings as Partial Replacement of Fine Aggregates in Concrete. In International Journal of Latest Technology in Engineering: Vol. VI. www.ijltemas.in

- Patel N., Dr. Hetal Pandya, (2022) Cost comparision of geopolymer concrete and m25 grade conventional concrete using compressive strength, International Research Journal of Modernization in Engineering Technology and Science, https://www.irjmets.com/uploadedfiles/paper/issue_4_april_2022/21352/final/fin_irjmets1650965173.pdf

- Provis, J. L., Palomo, A., & Shi, C. (2015). Advances in understanding alkali-activated materials. In Cement and Concrete Research (Vol. 78, pp. 110–125). Elsevier Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2015.04.013

- Qaisar Munir, Mariam Abdulkareem, Mika Horttanainen, Timo Kärki. (2023) A comparative cradle-to-gate life cycle assessment of geopolymer concrete. Science of the Total Environment https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0048969722083346sciencedirect

- Rahman, S. K., & Al-Ameri, R. (2022). Marine Geopolymer Concrete—A Hybrid Curable Self-Compacting Sustainable Concrete for Marine Applications. Applied Sciences (Switzerland), 12(6). https://doi.org/10.3390/app12063116

- Rajamane, N. P., Nataraja, M. C., & Lakshmanan, N. (2011). An introduction to geopolymer concrete. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/285666741_An_introduction_to_geopolymer_concrete

- Rangan, B. V. (2014). Geopolymer concrete for environmental protection Special Issue-Future concrete. In the Indian Concrete Journal. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/286116300.

- Ramesh, V., Muthramu, B., & Rebekhal, D. (2025). A review of sustainability assessment of geopolymer concrete through AI-based life cycle analysis. In AI in Civil Engineering (Vol. 4, Issue 1). Springer Nature. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43503-024-00045-3

- Rathnayaka M, Dulakshi Karunasinghe, Chamila Gunasekara, Kushan Wijesundara, Weena Lokuge, David W. Law, (2024) Machine learning approaches to predict compressive strength of fly ash-based geopolymer concrete: A comprehensive review. Construction and Building Materials https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0950061824006603

- Rawat, R., & Pasla, D. (2024). Mix design of FA-GGBS based lightweight geopolymer concrete incorporating sintered fly ash aggregate as coarse aggregate. Journal of Sustainable Cement-Based Materials, 13(8), 1164–1179. https://doi.org/10.1080/21650373.2024.2361266

- Ramujee, K., Sadula, P., Madhu, G., Kautish, S., Almazyad, A. S., Xiong, G., & Mohamed, A. W. (2024). Prediction of Geopolymer Concrete Compressive Strength Using Convolutional Neural Networks. Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences, 139(2), 1455–1486. https://doi.org/10.32604/CMES.2023.043384

- Rajalakshmi B,Mohamed Suhaib M, Shaahid Mohamood S, Sathish M. (2014) Comparison of geopolymer concrete with cement concrete, Journal of emerging technology and innovative research https://www.jetir.org/papers/JETIR2305533.pdf

- Rika Deni, Susanti, Ramlan Tambunan, Aazokhi Waruwu, Munajat Syamsuddin, (2018), Studies on concrete by partial replacement of cement with volcanic ash, Journal of Applied Engineering Science https://www.engineeringscience.rs/storage/old/pdf/doi10.5937jaes16-16494.pdf

- Riya Desai. (2025). Sustainable and Cost-Effective Alternatives to Cement in India for Construction. https://aquireacres.com/sustainable-and-cost-effective-alternatives-to-cement-in-india-for-construction

- Revathi, B., Gobinath, R., Bala, G. S., Nagaraju, T. V., & Bonthu, S. (2024). Harnessing explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) for enhanced geopolymer concrete mix optimization. Results in Engineering, 24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rineng.2024.103036

- Saloma, Siti Aisyah Nurjannah, Hanafiah, Arie Putra Usman, Steven Hu, Fathoni Usman, (2023) Behavior Of Geopolymer Concrete Wall Panels With Square Opening Variations Subjected To Cyclic Loads, Journal of Applied Engineering Science, doi.org/10.5937/jaes0-43777

- Siddiqi, M. A., Rizvi, M. U., Ahmed, J., & Tasleem, D. R. (2023). Effect Of Silica Fume On The Fresh And Hardened Concrete A Review (Vol. 11, Issue 6). www.ijcrt.org

- Shilar, F. A., Ganachari, S. V., Patil, V. B., & Nisar, K. S. (2022). Evaluation of structural performances of metakaolin based geopolymer concrete. Journal of Materials Research and Technology, 20, 3208–3228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2022.08.020

- Singh, S., Kumar, A., & Sitharam, T. G. (2023). Effect of red mud-based geopolymer binder on the strength development of clayey soil. Proceedings of the International Congress on Environmental Geotechnics, 267–275. https://doi.org/10.53243/ICEG2023-183

- Sobuz, M. H. R., Kabbo, M. K. I., Alahmari, T. S., Ashraf, J., GORGUN, E., & Khan, M. M. H. (2025). Microstructural behavior and explainable machine learning aided mechanical strength prediction and optimization of recycled glass-based solid waste concrete. Case Studies in Construction Materials, 22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2025.e04305

- Sonal, T., Urmil, D., & Darshan, B. (2022). Behaviour of ambient cured prestressed and non-prestressed geopolymer concrete beams. Case Studies in Construction Materials, 16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2021.e00798

- Strategic Market Research. (2024). Geopolymer Concrete Market Size 2030. https://www.strategicmarketresearch.com/market-report/geopolymer-concrete-market

- Swagato Das, Purnachandra Saha, Swatee Prajna Jena, Pratyush Panda (2022) Geopolymer concrete: Sustainable green concrete for reduced greenhouse gas emission–A review”, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2214785321076124

- Tamoor, M., & Zhang, C. (2025). Balancing Sustainability and Cost in Concrete Production: LCA of Foam, Geopolymer, Slag, and Agricultural Waste Concretes. ACS Sustainable Chemistry and Engineering, 13(36),14990–15006. https://doi.org/10.1021/ACSSUSCHEMENG.5C05321/SUPPL_FILE/SC5C05321_SI_002.PDF

- Tanakorn P. Chattarika P. (2018). A mix design procedure for alkali activated high calcium fly ash concrete cured at ambient temperature.

- Thaarrini J. & S.Dhivya (2016) Comparative Study on the Production Cost of Geopolymer and Conventional Concretes. International Journal of Civil Engineering Research, moz-extension://2ecd2d89-ba98-4322-bf6d-9907c548a683/enhanced-reader.html?openApp&pdf=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.ripublication.com%2Fijcer16%2Fijcerv7n2_03.pdf

- Uniyal, P., Gaur, P., Yadav, J., Bhalla, N. A., Khan, T., Junaedi, H., & Sebaey, T. A. (2025). A Comprehensive Review on the Role of Nanosilica as a Toughening Agent for Enhanced Epoxy Composites for Aerospace Applications. In ACS Omega (Vol. 10, Issue 16, pp. 15810–15839). American Chemical Society. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.4c10073

- USEPA Method 1311 (United States Environmental Protection Agency

- Verma, M., Dev, N., Rahman, I., Nigam, M., Ahmed, Mohd., & Mallick, J. (2022). Geopolymer Concrete: A Material for Sustainable Development in Indian Construction Industries. Crystals 2022, Vol. 12, 12(4). https://doi.org/10.3390/CRYST12040514

- Venkatesan, R. P., & Pazhani, K. C. (2016). Strength and durability properties of geopolymer concrete made with Ground Granulated Blast Furnace Slag and Black Rice Husk Ash. KSCE Journal of Civil Engineering, 20(6), 2384–2391. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12205-015-0564-0

- Verma M., Kamal Upreti, Prashant Vats, Sandeep Singh, Prashant Singh, Nirendra Dev, Durgesh Kumar Mishra, Basant Tiwari, (2022) Experimental Analysis of Geopolymer Concrete: A Sustainable and Economic Concrete Using the Cost Estimation Model , Advances in Materials Science and Engineering https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1155/2022/7488254

- Vijai, K., Kumutha, R., & Vishnuram, B. G. (2010). Effect of types of curing on strength of geopolymer concrete. In International Journal of the Physical Sciences (Vol. 5, Issue 9). http://www.academicjournals.org/IJPS

- Vora, P. R., & Dave, U. V. (2013). Parametric studies on compressive strength of geopolymer concrete. Procedia Engineering, 51, 210–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2013.01.030

- Yoo, S. Y.; J. J. Y. (2014). Investigation of the effects of different types of interlayers on floor impact sound insulation in box-frame reinforced concrete structures. Build. Environ. 2014, 76, 105–112.

- Zhang, B. et al. Durability of low-carbon geopolymer concrete: A critical review. Case Studies in Construction Materials (2024). https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S2214993724000629sciencedirect