Volume 24 number 1 article 1315 pages 61-71

Received: Oct 22, 2025 Accepted: Jan 16, 2026 Available Online: Feb 18, 2026 Published: Mar 02, 2026

DOI: 10.5937/jaes0-62324

CORAL ROCK ASH AS A SUPPLEMENTARY FILLER IN ASPHALT CONCRETE WEARING COURSE: LABORATORY PERFORMANCE AND MECHANISTIC–EMPIRICAL SERVICE-LIFE PREDICTION

Abstract

Flexible pavements with hot-mix asphalt (HMA) may underperform when conventional mineral filler provides insufficient mastic stiffness and moisture resistance. This study evaluates coral rock ash (CRA) as a partial replacement of conventional mineral filler in an asphalt concrete wearing course (AC–WC) mixture to improve laboratory performance and predicted service life. CRA was introduced at 0–10% of the total mixture mass, replacing an equivalent portion of filler in the gradation. Marshall stability/flow and indirect tensile strength (ITS, tensile strength) were measured at an optimum asphalt content of 6%. To link mixture-scale changes to structural performance, layer responses were computed using KENPAVE multilayer elastic analysis, where the HMA elastic modulus was derived from the ITS-based stiffness correlation used in the study (with Poisson’s ratio held constant), enabling mechanistic–empirical estimation of critical strains and allowable load repetitions. Regression analysis identified 4.8% CRA as optimal, yielding peak Marshall stability (1060.7 kg) and the smallest 7-day strength loss after 60 °C conditioning. Relative to the control, ITS increased by 22.6% (11.62→14.25, unit-consistent with the original dataset). In the mechanistic analysis, the improved mixture stiffness led to a reduction in bottom-HMA tensile strain (εt) and a corresponding increase in predicted allowable repetitions, extending the design life of the reference pavement section from 5 to 7 years. These findings indicate that CRA is a feasible, locally available supplementary filler for improving HMA performance and extending service life in coastal regions, provided that sourcing uses non-living, naturally stranded coral debris and complies with environmental regulations.

Highlights

- CRA used as filler replacement improved Marshall stability to ~1061 kg and met Bina Marga 2018 AC–WC limits.

- Marshall retained stability after 7-day 60°C conditioning remained ≥75% (Bina Marga criterion).

- ITS increased by 22.6% at 4.8% CRA, indicating stronger tensile resistance of the mix.

- KENPAVE M–E analysis (Indonesian design loading inputs) predicted life from 5 to 7 years for the modeled section.

Keywords

Content

1 Introduction

Flexible pavement is the dominant road type in Indonesia, largely due to its lower initial cost and constrained preservation budgets [1]. Rapid urban expansion has driven sustained traffic growth, increasing loading frequency and accelerating the accumulation of damage [2]. To manage cost and supply constraints, agencies have encouraged the use of locally available aggregates (e.g., crushed stone, iron sand) [3]. At the same time, Indonesia’s domestic asphalt supply reportedly covers only about half of the 1.2 million tons annual demand, making imports unavoidable and reinforcing the need for locally based innovations in asphalt materials and mix design [4].

Within this system, the asphalt surface layer is the primary load-carrying component and governs responses that control service life [5,6]. Pavement performance is therefore sensitive to base type, asphalt thickness, and interlayer conditions; weak bonding at the upper layers can rapidly translate traffic loading into cracking and deformation [7,8]. In Indonesia, field evidence shows that heavy-vehicle axle loads frequently exceed legal and planned limits, increasing the load transmitted through the pavement structure and accelerating damage accumulation and deterioration [9].

Hot-mix asphalt (HMA) comprises asphalt binder and aggregate, with mineral filler strongly influencing durability and moisture resistance [10,11]. Asphalt–filler physicochemical interactions can stiffen and structure the mastic, producing measurable changes in mixture response [12]. Yet, flexible pavements still suffer premature cracking, rutting, and durability loss due to moisture damage, weak subgrades, construction variability, and repeated loading; deformation is often aggravated at lower traffic speeds [13,14]. While improved quality control remains necessary [15], conventional HMA can still exhibit high air voids, moisture susceptibility, and limited durability [10,16]. Although recycled or aged constituents have been explored, they may introduce curing and uniformity challenges [17]. Mineral fillers can reduce porosity and enhance homogeneity, stiffness, and rutting resistance, but their effects are highly mix-specific and dosage-dependent [18–20].

Coastal zones generate substantial coral rock waste as dead coral colonies erode and are transported to shore, particularly following bleaching and subsequent sediment deposition [21]. Most engineering research on coral-derived materials has focused on sands/powders in cementitious systems and eco-mortar, or on built structures for reef restoration, rather than asphalt mixtures [22–25]. Moreover, coral rock’s high porosity and relatively low compressive strength (9.91 MPa; porosity 48.5 ± 5.4%) mean its particle morphology and pore structure can strongly affect mechanical behavior, raising uncertainty when repurposed as fines in a bituminous matrix [26–28]. Despite expanded mapping of global coral habitat (348,361 km², with significant coverage in Indonesian waters) and growing interest in circular-economy pathways [29–32], key questions remain unresolved for coral rock ash (CRA) in HMA: (i) whether CRA can function effectively as a supplementary filler to improve mixture stability and moisture-related durability; (ii) what dosage window yields benefits without inducing bleeding or brittleness; and (iii) how mixture-scale improvements translate into mechanistic–empirical performance metrics (critical strains and predicted service life) under field-representative loading.

Against this backdrop, the present study investigates coral rock ash (CRA), a finely ground ash derived from coral rock waste, as a supplementary mineral filler in HMA to improve mixture performance and extend pavement design life, particularly for coastal applications where CRA is locally available. We combine laboratory testing (Marshall stability/flow and indirect tensile strength) with mechanistic–empirical (M–E) multilayer elastic analysis in KENPAVE to quantify critical strains and predict service-life impacts under field-representative loading. Unlike prior studies that typically report laboratory performance of alternative fillers without translating the measured mixture properties into structural responses and life predictions, this work provides an integrated lab-to-design pathway for coral rock ash (CRA) in AC–WC. Specifically, the study offers three original contributions: (i) a dose–response quantification of CRA as a partial filler replacement (0–10% by total mix mass) benchmarked against a control mixture to identify an optimum range rather than a single trial dosage; (ii) a mechanistic linkage that propagates measured mixture properties into an M–E framework to estimate bottom-HMA tensile strain and allowable load repetitions, thereby converting laboratory improvements into predicted service-life gains; and (iii) a deployment-focused sustainability perspective, defining responsible sourcing of naturally stranded, non-living coral debris and framing compliance with environmental regulations to support coastal implementation while reducing reliance on imported asphalt and virgin mineral resources.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Object and hypothesis of the study

The objective of this research is to develop an optimized Hot Mix Asphalt (HMA) mixture. More precisely, Asphalt Concrete - Wearing Course (AC-WC) is the predominant type of pavement utilized in Indonesia, by incorporating coral rock ash. The underlying hypothesis is that AC-WC mixtures often contain numerous voids, and attempts to address these voids by increasing asphalt content may result in bleeding. Therefore, the inclusion of supplementary ingredients becomes imperative to mitigate void formation within the mixture. The varying proportions of coral rock ash added to the mixture are expected to influence its mechanical performance. Consequently, this study seeks to elucidate the impact of coral rock ash as a filler on the mechanical properties and characteristics of the AC-WC mixture.

2.2 Materials

The mix-forming materials used in this study consisted of locally sourced coarse and fine aggregates that comply with the Indonesian AC–WC requirements [34]. The asphalt binder was 60/70 penetration grade asphalt (Pertamina) obtained from a local distributor and is widely used in road pavement mixtures [35]. To ensure reproducibility and enable comparison with other studies, the key physical properties of the asphalt binder (including penetration, softening point, and viscosity) are summarized in Table 1.

The supplementary material investigated in this study was coral rock ash (CRA), produced from naturally stranded, non-living coral rock debris that has been transported to the coast by ocean currents. The collected material was oven-dried and then pulverized by grinding to obtain a fine ash, as shown in Fig. 2. In this manuscript, the term “stone ash” refers to mineral filler/fines (passing the 0.075 mm sieve) commonly used in Indonesian asphalt mixtures as a filler component, rather than combustion ash. The physical properties of the aggregates and filler are also reported in Table 1.

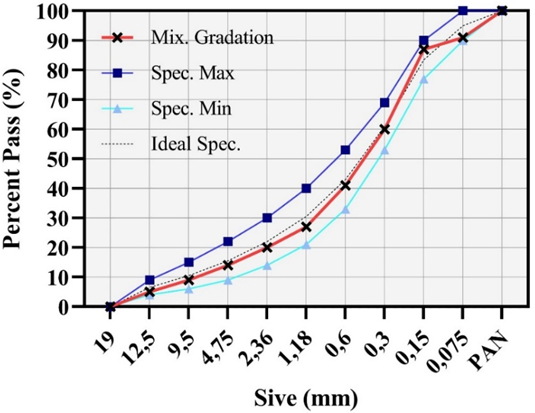

The aggregate blend for the AC–WC mixture was prepared using three size fractions (1–2, 0.5–1, and filler/stone ash) to satisfy the target gradation envelope specified in [34]. The selected blend proportions were 15% coarse aggregate, 30% fine aggregate, and 55% filler/stone ash, following the gradation design adopted for this study [34]. The resulting combined gradation curve and its compliance with the AC–WC specification limits are presented in Fig. 1. This full gradation disclosure clarifies the aggregate composition and provides a transparent basis for replication and mechanistic interpretation.

Table 1. Asphalt binder and aggregate properties

| No | Properties | Course Aggregate | Fine Aggregate | Stone Ash | Asphalt | Specification |

| 15% | 30% | 55% | ||||

| 1 | Specific Gravity of Aggregates a) Bulk b) SSD c) Apparent d) Absorption | 2.56 2.62 2.73 2.45 | 2.46 2.52 2.62 2.35 | 2.59 2.71 2.51 2.87 | - | 2.4 – 2.9 2.4 – 2.9 2.4 – 2.9 ≤ 3 % |

| 2 | Fill Weight a) Loose (gr/cm3) b) Dense (gr/cm3) | 1,42 1.50 | 1.44 1.52 | 1.52 1.80 | - | 1,4 – 1,9 1,4 – 1,9 |

| 3 | Sand Equivalent a) Before loading (%) b) After loading (%) | - - | - - | 82.92 80.82 | - | ≥ 60 % |

| 4 | Los Angeles Abrasion (%) | 24.20 | 26.80 | - | - | ≤ 40 % |

| 5 | Aggregate Adhesion to Asphalt (%) | - | - | - | 96 | ≥ 95 % |

| 6 | Penetration 25oC;100 gr; 5 seconds; 0,1 mm | - | - | - | 62.60 | 60 – 79 |

| 7 | Specific Gravity of Asphalt | - | - | - | 1.04 | 1.0 – 1.16 |

| 8 | Soft Point of Asphalt (°C) | - | - | - | 53 | ≥ 48 |

| 9 | Ductility, 25 oC; cm | - | - | - | 152.50 | ≥ 100 |

| 10 | Viscosity, 120 oC; cts | - | - | - | 633.59 | - |

Fig.1. Aggregate gradation

2.3 Experimental procedures

The asphalt content utilized in the design ranges from 4.5% to 6.5%. The Marshall characteristics test analyzes the correlation between stability, flow, Void In Mix, Void Mineral Aggregate, and Void Field Bitumen as shown in Table 2. Based on the test results, the optimal asphalt content (OAC) is 6%. The OAC value is an independent variable to assess the mixture's ability to withstand stability, durability, modulus of elasticity, and permanent deformation. Rock ash additives are incorporated in five variations, ranging from 2% to 10% based on the weight of rock ash in the mix. Analysis results are derived from the average repetition values of three test specimens for the Marshall stability test. Subsequently, the optimum coral ash value is determined based on the Marshall stability value, serving as a reference for creating test specimens and analyzing each test. The obtained results are subsequently compared to the Asphalt Concrete-Wearing Course (AC-WC) mixture, excluding the incorporation of coral rock ash.

Table 2. Marshall test result

| Properties of Mixtures | Test Results | Spesification | ||||

| Asphalt content; % | 4.5 | 5 | 5.5 | 6 | 6.5 | |

| Density | 2,255 | 2,263 | 2,272 | 2,273 | 2,275 | ≥2.2 kg/mm3 |

| VIM; % | 6,765 | 5,775 | 4,772 | 4,053 | 3,333 | 3-5% |

| VMA; % | 15,088 | 15,225 | 15,357 | 15,745 | 16,135 | ≥ 15 % |

| VFA; % | 55,173 | 65,092 | 68,961 | 74,289 | 79,355 | ≥ 63 % |

| Stability; kg | 951,054 | 1015,282 | 1035,132 | 994,546 | 955,340 | 800 – 1800 kg |

| Flow; mm | 3,33 | 3,13 | 3,00 | 3,03 | 3,40 | 2-4 mm |

| MQ; kg/mm | 287,640 | 324,368 | 345,089 | 328,020 | 275,793 | Min. 250 kg/mm |

The analysis results are obtained from the average value of the repetition of three test objects, as follows:

a) Marshall retained stability testing is conducted through immersion for 24 hours, two days, four days, and seven days in a soaking bath at a temperature of approximately 60°C. Subsequently, the specimens are tested using a Marshall tool in accordance with ASTM D-6927;

b) Indirect tensile strength testing entails applying a single or repeated load in a direction parallel to the diameter path of the specimen, following the guidelines of ASTM D 4123-82.

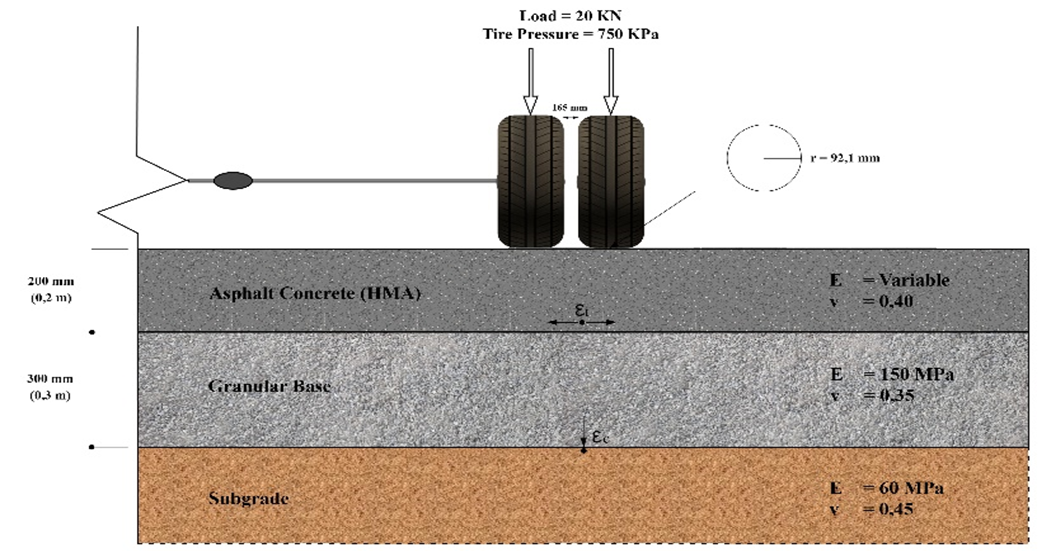

In designing the pavement based on the Mechanistic-Empirical approach, the KENLAYER software is employed. This software treats the pavement system as an elastic multi-layer system, with each layer possessing specified properties and extending horizontally. Additionally, the KENPAVE software facilitates the analysis of elastic multi-layer systems under circularly loaded areas, aiding in determining pavement responses at predetermined points. The durability of pavement structures is evaluated utilizing the KENLAYER software [36].

The pavement section under consideration comprises three layers, aligning with typical pavements in Indonesia. The top layer is a Hot Mix Asphalt (HMA) concrete asphalt surface layer, 200 millimeters thick, overlaid on a granular base layer with a total thickness of 300 millimeters. The bottom layer consists of a compacted subgrade of infinite thickness. Each layer is characterized by its respective E and Poisson's ratio, using the elastic modulus obtained from the outcomes of indirect tensile testing. Furthermore, the subgrade and foundation layer soils are determined based on typical pavements in Indonesia [37].

This pavement structure corresponds to the full-depth flexible pavement type. The traffic load is represented by dual tires with a circular tire tread area having a radius of 92.1 mm and a tire pressure of 750 Kilo Pascal (kPa), in accordance with the standard axle tire configuration outlined in the Indonesian pavement design manual [37]. The pavement properties used are shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 2. Coral Rock Ash

Fig. 3. Flexible Pavement Structure

To assess the critical response of the asphalt concrete layer and its susceptibility to fatigue cracking, the analysis explicitly examines the tensile strain at the bottom of the layer, emphasizing the strain occurring at the center of the load wheel. The critical strain for stress can be calculated as follows:

| $N_f = 0.796\,(\varepsilon_t)^{-3.291}\,(E)^{-0.854}$ | (1) |

where Nf – the number of load repetitions allowed to control fatigue cracking; ɛt – horizontal tensile strain at the bottom of the asphalt concrete layer; E – modulus of elasticity of the HMA.

3 Result and discussion

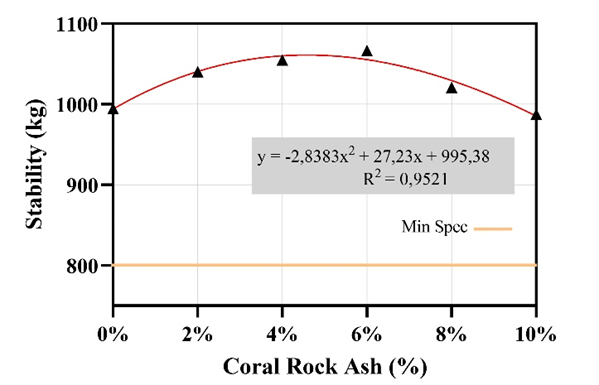

The Marshall stability results for mixtures with and without coral rock ash (CRA) are compared in Fig. 3. All mixtures containing CRA in the range of 0–10% satisfy the specification limits [34]. Stability increases with CRA content and reaches the highest measured value of 1066.556 kg at 6% CRA. Beyond this level, stability decreases, which is consistent with over-filling effects that can promote an overly rich mastic (fatness/bleeding) and reduce aggregate interlock by effectively increasing binder–mastic dominance in the load-carrying skeleton. Similar dose-dependent behavior has been reported for mixtures with increasing filler contents [38]. Overall, the stability response confirms that CRA can enhance load-bearing capacity within an appropriate dosage window while maintaining compliance with [34].

To determine an optimum CRA content for subsequent testing and mechanistic–empirical (M–E) evaluation, regression analysis was used to identify the peak of the fitted stability–dosage curve rather than relying solely on the single highest experimental point. Although the maximum observed stability occurs at 6% CRA, the regression-based optimum (4.8%) represents the estimated peak of the overall trend while accounting for experimental variability across dosage levels and avoiding selection driven by a potentially local, point-specific maximum. This approach is consistent with mixture design practice, where the selected optimum is commonly based on the overall response pattern and balanced performance, particularly when the stability curve begins to show diminishing returns and early signs of over-filling at higher dosages.

Fig. 4. Effect of coral rock ash on stability

To determine the optimum value of the Marshall test, regression statistical analysis employing a polynomial line was utilized. This approach enabled the derivation of an equation representing the relationship between stability value and coral rock ash content:

| \[y=-2.8383x^2+27.23x+995.38\] | (2) |

where y – the stability value of the mixture and x – the variation of coral ash content. To determine the peak value of the polynomial line using equation (2), a stability value of 1060.694 kg was obtained with an optimum coral rock ash content of 4.8%. This optimum variation will be used as a reference for subsequent tests.

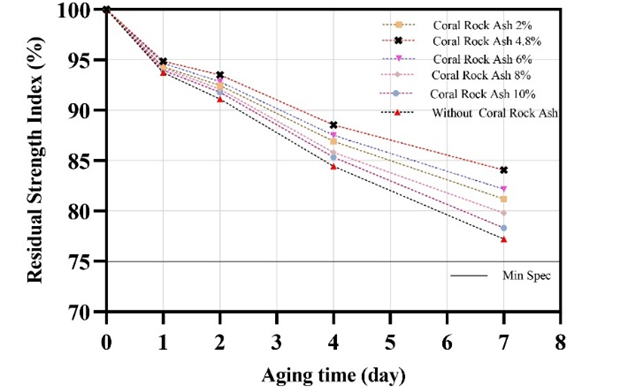

This optimal variation will serve as the reference for subsequent tests. As depicted in Fig. 4, the relationship between the residual strength index and soaking duration (days) is illustrated. The residual strength index values exhibit a decline with increasing soaking duration, regardless of the presence or absence of coral rock ash. Specifically, variations in soaking duration of 1, 2, 4, and 7 days demonstrate decreasing residual strength index values.

Several factors may contribute to this reduction in residual strength, including prolonged soaking duration and dynamic water sourcing [39]. As the asphalt mixture remains submerged in water for an extended period, the properties of the asphalt binder change, resulting in diminished strength and, consequently, reduced performance of the mixture.

Similar research was conducted using lime and cement containing carbon as filler; the same trend value was obtained [38, 40]. This is explained by the content of calcium carbonate (CaCO3) reacting with water and then settling on the surface of the aggregate, causing the surface roughness to increase [40]. This increase in roughness further enhances the adhesion between aggregate and asphalt [41].

Coral rock ash, as an additive material, effectively occupies voids within the mixture, resulting in improved compaction and enhanced durability of asphalt concrete. Moisture damage, typically observed in mixtures lacking coral ash, often stems from large air voids and poor adhesion between asphalt and aggregate [42].

Notably, the utilization of coral rock ash mitigates this decline, albeit to a lesser extent compared to mixtures without coral rock ash. This can be attributed to the calcium carbonate content in coral rock ash, which enhances adhesion between mixtures and maintains results meeting the predetermined requirement of ≥ 75% [34].

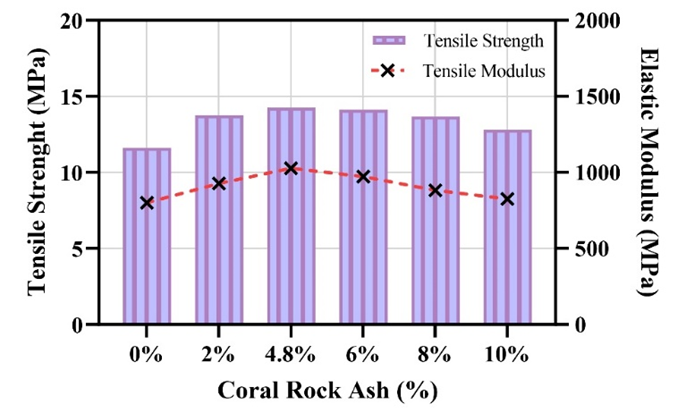

Fig. 5. Effect of coral rock ash on residual strength index

In Fig. 5, it is evident that incorporating coral rock ash as an additive material increases the tensile strength value. This enhancement can be attributed to the presence of the chemical compound CaCO3 in coral rock ash. Through this test, the optimal coral ash content was determined to be 4.8%, resulting in a tensile strength value of 14.25 MPa. A higher tensile strength in the mixture enables it to withstand greater tensile strain, thereby reinforcing its resistance to crack formation, particularly wide cracks that could compromise the road structure. However, this reinforcement is only effective at the optimal level; excessive addition of coral rock ash can lead to increased cracking and reduced durability under repeated loads. Similarly, research on Reclaimed Asphalt Pavement mixtures aimed at enhancing pavement performance has revealed that excessive levels of additives can diminish the tensile strength of the mixture [42]. This behavior is also observed when an excessive use of additives leads to reduced performance in terms of tensile strength [43].

The relationship between elastic modulus and strain is inversely proportional; higher elastic modulus values correspond to lower strain values. This indicates that mixtures with higher elastic modulus values are more resistant to deformation. The behavior of the elastic modulus can be influenced by various factors, including the addition of additives and heat treatment. However, as the percentage of coral rock ash exceeds 4.8%, there is a notable decrease in the mixture's ability to regain its shape after experiencing elastic deformation.

Fig. 6. Effect of coral rock ash on indirect tensile strength

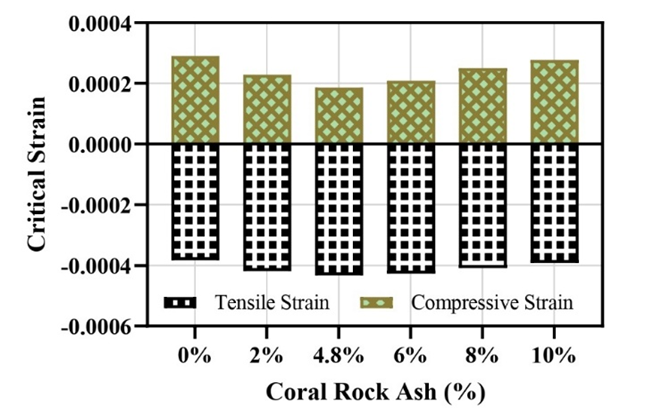

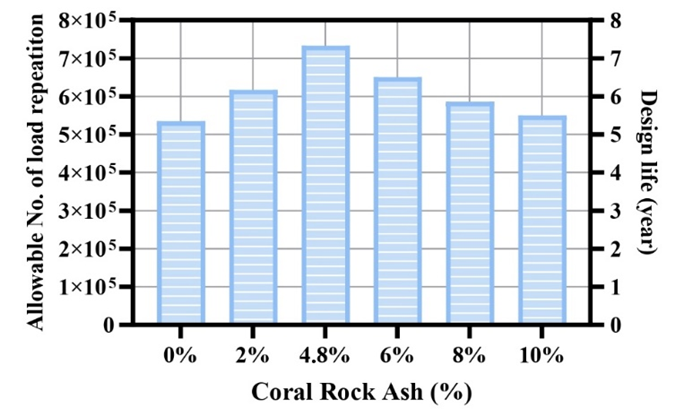

Fig. 6 and 7 illustrate the reaction of the pavement structure to the weight of vehicles, with a specific emphasis on the maximum stretching of the material under the asphalt layer, the maximum compression of the material above the subgrade, the number of times the load may be applied without causing damage, and the expected lifespan of the pavement. These findings were derived from KENPAVE software simulations. Notably, incorporating coral rock ash (CRA) into the asphalt concrete surface course reduces the critical tensile strain at the bottom of the HMA layer (εt) and reduces the compressive strain (εz) above the subgrade, compared with the control mixture without CRA. This trend is mechanistically consistent with fatigue theory: a lower εt increases the allowable load repetitions and therefore extends predicted fatigue life. Accordingly, any earlier statement indicating that CRA ‘raises tensile strain’ should be interpreted as a wording inconsistency and should be aligned with the strain outputs used in the mechanistic–empirical life prediction.

Fig. 7. Effect of coral rock ash on flexible pavement critical strain

Fig. 8. Effect of coral rock ash on flexible pavement service life

The observed reduction in compressive strain above the subgrade indicates that coral rock ash (CRA) can improve resistance to permanent deformation and rutting, which is consistent with findings that modified mixtures may enhance durability-related responses [45]. In parallel, CRA increases mixture tensile strength and improves binder–aggregate adhesion, which can reduce crack susceptibility under repeated loading; this interpretation is in line with prior studies reporting that additives may enhance tensile-related performance in asphaltic systems [44].

Regarding fatigue, it should be noted that the mechanistic–empirical prediction links service life primarily to the critical tensile strain at the bottom of the HMA layer and the associated allowable load repetitions. Therefore, the reported improvement in predicted fatigue life is attributed to the strain response output by KENPAVE under the adopted inputs, rather than to a generic “increase” in tensile strain.

As shown in Fig. 7, integrating 4.8% CRA into the HMA surface course increases the predicted design life of the reference pavement section from approximately 5 years to 7 years under the specific traffic loading, tire pressure, layer thicknesses, and climatic/temperature assumptions adopted in this study (as defined in the mechanistic–empirical input set). This result should be interpreted as a scenario-based prediction for the modeled pavement configuration rather than a universal service-life gain. Because the analysis is based on a single pavement structure and loading case, the magnitude of life extension may vary with traffic spectra, climate/temperature regime, layer thickness, and base/subgrade stiffness.

Nevertheless, the trend observed here supports the potential of CRA as a supplementary filler to enhance mixture performance and improve fatigue-related outcomes when appropriately dosed. This is consistent with related work showing that calcium-carbonate-bearing fillers and fine mineral additives can improve mixture quality and fatigue performance [46]. The beneficial effect is plausibly associated with microfiller densification and improved mastic structure and adhesion, although broader validation across multiple structures, climates, and traffic levels is recommended.

4 Conclusions

This study shows that coral rock ash (CRA) can improve selected performance indicators of AC–WC hot-mix asphalt when used as a partial replacement of conventional mineral filler, assessed at an optimum asphalt content of 6%. CRA varied from 0–10% by total mixture mass, and the following improvements were observed relative to the control mix.

First, CRA increased Marshall stability within an effective dosage window. The highest measured stability was 1066.556 kg at 6% CRA, while a polynomial regression across the full dosage range identified 4.8% CRA as the regression-based optimum (peak of the fitted stability–dosage curve) with a predicted stability of ≈1060.7 kg. The 4.8% dosage was selected for subsequent testing because it represents the estimated optimum of the overall response while reducing the risk of over-filling effects (fatness/bleeding) that become evident as stability begins to decline beyond the peak.

Second, CRA improved moisture-conditioning durability. After prolonged hot-water conditioning at 60 °C, retained stability at the selected dosage remained above the specification threshold, and the 7-day retained stability was about 7% higher than the control under the same conditioning.

Third, CRA increased indirect tensile strength (ITS) by 22.6. Mechanistically, the higher ITS indicates a stronger and more coherent mastic–aggregate system and improved resistance to tensile failure initiation, which supports enhanced cracking tolerance under repeated loading, provided the mixture does not become overly stiff or brittle at higher CRA contents.

When these measured properties were propagated into the mechanistic–empirical multilayer elastic analysis (KENPAVE) for a single reference pavement structure and loading condition (as defined in the Methods, including layer thicknesses, tire pressure, and temperature/modulus assumptions), the critical bottom-HMA tensile strain (εt) decreased for the CRA optimum case, leading to a higher allowable number of repetitions and a scenario-based increase in predicted service life from 5 to 7 years. This conclusion is valid only if the strain trend reported in Results is consistent with the KENPAVE outputs used for life prediction; therefore, any statement in the Results and Discussion indicating that CRA “increases εt” should be corrected to reflect the strain values actually used in the fatigue calculation.

From a deployment perspective, CRA has the potential to support circular use of locally available coastal debris and reduce reliance on hauled mineral filler, especially in archipelagic regions. However, this should be treated as a prospective benefit rather than a quantified environmental outcome in the absence of a life-cycle assessment and leaching verification.

Future work should directly address the present limitations by: (i) confirming stiffness and rutting performance using ITSM/|E*| and Hamburg wheel tracking, (ii) adding statistical inference (ANOVA/CI) and uncertainty propagation for M–E inputs, (iii) validating mechanistic predictions via accelerated loading or field trials under tropical temperatures and moisture cycles, (iv) characterizing CRA particle size/mineralogy variability and CRA–binder interactions using FTIR/SEM and rheology, and (v) conducting leaching tests (TCLP/EN/SNI) and a screening LCA to evaluate environmental compliance and net CO₂/energy impacts for coastal applications.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the Road Pavement Materials Laboratory, Department of Civil Engineering, Universitas Muslim Indonesia, for access to facilities and technical assistance during the experimental program.

References

- A. Mulyawan, S. M. Saleh, and R. Anggraini, “Simulation of road treatment costs based on life-cycle cost analysis,” IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng., vol. 933, no. 1, 2020, doi: 10.1088/1757-899X/933/1/012024.

- M. Mohammadi, A. Dideban, and B. Moshiri, “A Novel Approach to Modular Control of Highway and Arterial Networks using Petri Nets Modeling,” Int. J. Eng. Trans. B Appl., vol. 36, no. 8, pp. 1578–1588, 2023, doi: 10.5829/ije.2023.36.08b.17.

- L. Siahaya, B. S. Subagio, and A. J. Susilo, “Development of Flexible Pavement Structure Using the Local Materials of Sarmi, Papua, Indonesia - Based on Indonesian National Specification,” Int. J. GEOMATE, vol. 24, no. 103, pp. 34–41, 2023, doi: 10.21660/2023.103.3479.

- V. I. G. Djerol, L. Djakfar, C. W. Kartikowati, R. Kusumaningrum, and M. Miftahulkhair, “Crack Resistance Analysis of Buton Asphalt Wearing Course: Modification with Eco Biopolymer Carrageenan Using Three Point Bending Test,” Civil Engineering and Architecture, vol. 13, no. 2, pp. 1317–1325, 2025, doi: 10.13189/cea.2025.130242.

- M. Miftahulkhair, M. Z. Arifin, and F. R. Sutikno, “Revealing the impact of losses on flexible pavement due to vehicle overloading”, EEJET, vol. 2, no. 1 (128), pp. 55–63, Apr. 2024. doi: 10.15587/1729-4061.2024.299653.

- Q. Pan et al., “Field measurement of strain response for typical asphalt pavement,” J. Cent. South Univ., vol. 28, no. 2, pp. 618–632, Feb. 2021, doi: 10.1007/s11771-021-4626-9.

- H. Wang and X. Dong, “Analysis of the Mechanical Response of Asphalt Pavement with Different Types of Base,” in Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering, Springer International Publishing, 2020, pp. 849–865. doi: 10.1007/978-981-15-2349-6_56.

- M. De Beer, “Weak Interlayers Found in Flexible and Semi-flexible Road Pavements,” in 8th RILEM International Conference on Mechanisms of Cracking and Debonding in Pavements, A. Chabot, W. G. Buttlar, E. V Dave, C. Petit, and G. Tebaldi, Eds., Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, 2016, pp. 425–430. doi: 10.1007/978-94-024-0867-6_59.

- M. Miftahulkhair, M. Z. Arifin, and F. R. Sutikno, “Effects of using lannea coromandelica gum and coal waste in hot mix asphalt pavement on vehicle overloading,” IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci., vol. 1416, no. 1, 2024, doi: 10.1088/1755-1315/1416/l/012042.

- S. Sunarjono, N. Hidayati, M. W. S. Aji, W. F. Cindikia, and A. Magfirona, “The Improvement of Asphalt Mixture Durability Using Portland Cement Filler and Rice Husk Ash,” Civ. Eng. Archit., vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 1091–1098, 2023, doi: 10.13189/cea.2023.110240.

- U. Gazder, M. Arifuzzaman, U. Shahid, and A. A. Mamun, “Effect of fly ash and lime as mineral filler in asphalt concrete,” in Advances in Materials and Pavement Performance Prediction, CRC Press, 2018, pp. 373–377. doi: 10.1201/9780429457791-71.

- J. Hou, X. Ma, H. Chen, and Z. Wang, “A comparison of indices used to evaluate asphalt-filler interactions,” Constr. Build. Mater., vol. 359, no. 126, p. 129501, 2022, doi: 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.129501.

- I. Saidakberova, S. Yadgarov, B. Qurbonov, and Z. Pulatova, “Influence of climatic conditions on the occurrence of wheel track deformation on asphalt paved roads,” E3S Web Conf., vol. 264, pp. 2–8, 2021, doi: 10.1051/e3sconf/202126402028.

- M. G. Uljarević, S. Z. Milovanović, R. B. Vukomanović, and D. D. Zeljić, “Geotechnical problems in flexible pavement structures design,” Geomech. Eng., vol. 32, no. 1, pp. 35–47, 2023, doi: 10.12989/gae.2023.32.1.035.

- X.-P. Ou, K. Ding, W.-L. Xu, F. Gao, and L. Jiang, “Discussion on construction technology of asphalt pavement on expressway,” in Civil Engineering and Urban Planning III, K. Mohammadian, K. G. Goulias, E. Cicek, J.-J. Wang, and C. Maraveas, Eds., CRC Press, 2014, pp. 151–154. doi: 10.1201/b17190.

- O. Sirin, M. Gunduz, and M. E. Shamiyeh, “Assessment of Pavement Performance Management Indicators Through Analytic Network Process,” IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag., vol. 69, no. 6, pp. 2684–2692, 2022, doi: 10.1109/TEM.2019.2952153.

- B. Gómez-Meijide, H. Ajam, P. Lastra-González, and A. Garcia, “Effect of ageing and RAP content on the induction healing properties of asphalt mixtures,” Constr. Build. Mater., vol. 179, pp. 468–476, 2018, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.05.121.

- J. Wang, M. Guo, and Y. Tan, “Study on application of cement substituting mineral fillers in asphalt mixture,” Int. J. Transp. Sci. Technol., vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 189–198, 2018, doi: 10.1016/j.ijtst.2018.06.002.

- A. Kuity and A. Das, “Estimation of Appropriate Filler Quantity in Asphalt Mix from Microscopic Studies,” in 8th RILEM International Symposium on Testing and Characterization of Sustainable and Innovative Bituminous Materials, F. Canestrari and M. N. Partl, Eds., Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, 2016, pp. 49–59. doi: 10.1007/978-94-017-7342-3_5.

- J. Choudhary, B. Kumar, and A. Gupta, “Utilization of solid waste materials as alternative fillers in asphalt mixes: A review,” Constr. Build. Mater., vol. 234, p. 117271, 2020, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.117271.

- J. Morais, R. Morais, S. B. Tebbett, and D. R. Bellwood, “On the fate of dead coral colonies,” Funct. Ecol., vol. 36, no. 12, pp. 3148–3160, Dec. 2022, doi: 10.1111/1365-2435.14182.

- A. B. Paxton et al., “What evidence exists on the ecological and physical effects of built structures in shallow, tropical coral reefs? A systematic map protocol,” Environ. Evid., vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 1–17, 2023, doi: 10.1186/s13750-023-00313-2.

- L. Ma, J. Wu, M. Wang, L. Dong, and H. Wei, “Dynamic compressive properties of dry and saturated coral rocks at high strain rates,” Eng. Geol., vol. 272, no. September 2019, p. 105615, Jul. 2020, doi: 10.1016/j.enggeo.2020.105615.

- J. Zhang, Z. Wu, Y. Zhang, Q. Fang, H. Yu, and C. Jiang, “Mesoscopic characteristics and macroscopic mechanical properties of coral aggregates,” Constr. Build. Mater., vol. 309, no. September, p. 125125, 2021, doi: 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.125125.

- K. Amarsingh Bhabu, J. Theerthagiri, J. Madhavan, T. Balu, G. Muralidharan, and T. R. Rajasekaran, “Cubic fluorite phase of samarium doped cerium oxide (CeO2)0.96Sm0.04 for solid oxide fuel cell electrolyte,” J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron., vol. 27, no. 2, pp. 1566–1573, 2016, doi: 10.1007/s10854-015-3925-z.

- M. B. Lyons et al., “New global area estimates for coral reefs from high-resolution mapping,” Cell Reports Sustain., p. 100015, 2024, doi: 10.1016/j.crsus.2024.100015.

- J. Wei, Z. Chen, J. Liu, J. Liang, and C. Shi, “Review on the characteristics and multi-factor model between pore structure with compressive strength of coral aggregate,” Constr. Build. Mater., vol. 370, no. October 2022, p. 130326, 2023, doi: 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.130326.

- L. Lizárraga-Mendiola, L. D. López-León, and G. A. Vázquez-Rodríguez, “Municipal Solid Waste as a Substitute for Virgin Materials in the Construction Industry: A Review,” Sustain., vol. 14, no. 24, 2022, doi: 10.3390/su142416343.

- D. A. Rasool, H. H. Al-Moameri, and M. A. Abdulkarem, “Review of Recycling Natural and Industrial Materials Employments in Concrete,” J. Eng. Sustain. Dev., vol. 27, no. 2, pp. 180–195, 2023, doi: 10.31272/jeasd.27.2.3.

- Y. qian Ni, J. yan Shi, Z. hai He, M. yang Jin, M. fei Yi, and A. S. Jamal, “Synergistic effect of coral sand and coral powder on the performance of eco-friendly mortar,” Constr. Build. Mater., vol. 411, no. December 2023, p. 134468, 2024, doi: 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.134468.

- Q. Qin, Q. Meng, M. Gan, Z. Ma, and Y. Zheng, “Deterioration mechanism of coral reef sand concrete under scouring and abrasion environment and its performance modulation,” Constr. Build. Mater., vol. 408, no. September, p. 133607, 2023, doi: 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.133607.

- X. Zhang, X. Liu, Y. Xu, G. Wang, and M. Zang, “Fragmentation modes of single coral particles under uniaxial compression: Microstructural insights,” Constr. Build. Mater., vol. 344, no. January, p. 128186, 2022, doi: 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.128186.

- Z. Liu et al., “Identification of bending fracture characteristics of cement-stabilized coral aggregate in four-point bending tests based on acoustic emission,” Constr. Build. Mater., vol. 402, no. April, p. 132999, 2023, doi: 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.132999.

- Ministry of Public Works and Housing and Directorate General of Highways, “General Specifications of Bina Marga 2018 for Road Works and Bridges,” 2018. [Online]. Available: https://binamarga.pu.go.id/uploads/files/425/spesifikasi-umum-2018.pdf

- J. Zhang, J. Peng, A. Zhang, and J. Li, “Prediction of permanent deformation for subgrade soils under traffic loading in Southern China,” Int. J. Pavement Eng., vol. 23, no. 3, pp. 673–682, 2022, doi: 10.1080/10298436.2020.1765244.

- Y. H. Huang, Pavement Analysis and Design, no. v. 2. in Pavement Analysis and Design. Pearson Prentice Hall, 2004. [Online]. Available: https://books.google.ie/books?id=5gR6swEACAAJ

- Directorate General of Highway, “The Manual of Pavement Design Guide No. 02/M/BM/2017,” Jakarta: Indonesia, 2017. [Online]. Available: https://simk.bpjt.pu.go.id/file_uploads/ketentuan/MDP_(Revisi-2017_Palembang)_pdf_28-12-2021_08-47-17.pdf

- A. H. Aljassar, S. Metwali, and M. A. Ali, “Effect of filler types on Marshall stability and retained strength of asphalt concrete,” Int. J. Pavement Eng., vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 47–51, 2004, doi: 10.1080/10298430410001733491.

- M. Guo, T. Nian, P. Li, and V. P. Kovalskiy, “Exploring the short-term water damage characteristics of asphalt mixtures: The combined effect of salt erosion and dynamic water scouring,” Constr. Build. Mater., vol. 411, no. July 2023, p. 134310, 2024, doi: 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.134310.

- B. Singh and S. Jain, “Effect of lime and cement fillers on moisture susceptibility of cold mix asphalt,” Road Mater. Pavement Des., vol. 23, no. 10, pp. 2433–2449, 2022, doi: 10.1080/14680629.2021.1976254.

- G. Raymond and D. Lesueur, “Adhésion liant granulat,” in Matériaux routiers bitumineux 1 : description et propriétés des constituants, HERMES SCIENCE (29 july2004), 2004, pp. 177–203.

- C. Ling, A. Hanz, and H. Bahia, “Measuring moisture susceptibility of Cold Mix Asphalt with a modified boiling test based on digital imaging,” Constr. Build. Mater., vol. 105, pp. 391–399, 2016, doi: 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2015.12.093.

- A. Laomuad, A. Suddeepong, S. Horpibulsuk, and A. Buritatum, “Evaluating polyethylene terephthalate in asphalt concrete with reclaimed asphalt pavement for enhanced performance,” Constr. Build. Mater., vol. 422, no. October 2023, p. 135749, 2024, doi: 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.135749.

- I. Mirzadeh, R. Shirinabadi, G. Mohammadi, and S. H. Lajevardi, “Direct and Indirect Tensile Behavior of Cement-Zeolite-amended Sand Reinforced with Kenaf Fiber,” Int. J. Eng. Trans. B Appl., vol. 37, no. 05, pp. 818–832, 2024, doi: https://doi.org/10.5829/ije.2024.37.05b.01.

- H. J. Aljbouri and A. H. Albayati, “Effect of nanomaterials on the durability of hot mix asphalt,” Transp. Eng., vol. 11, no. January, p. 100165, 2023, doi: 10.1016/j.treng.2023.100165.

- A. Mondal and G. D. R. R.N., “Evaluating the engineering properties of asphalt mixtures containing RAP aggregates incorporating different wastes as fillers and their effects on the ageing susceptibility,” Clean. Waste Syst., vol. 3, no. July, p. 100037, 2022, doi: 10.1016/j.clwas.2022.100037.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Supplementary Materials

The authors declare that there are no supplementary materials associated with this article.